It’s maple syrup season up here in New England, which means I spent most of yesterday in my brother’s sugar shack watching sap boil and teaching my son things like how to carry logs, stack wood, and sample the syrup. Maple syrup making is a fun process, mostly because there’s enough to do to make it interesting, but not so much to do that you can’t be social while doing it.

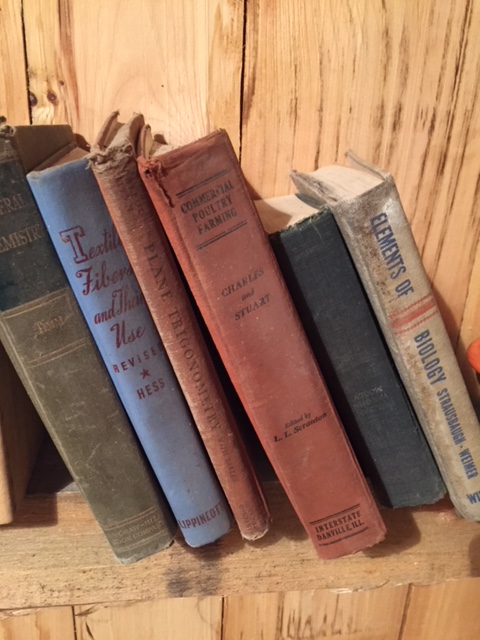

During the course of the day, my brother mentioned that he had found an old stack of my grandfather’s textbooks, published in the 1940s:

Since he’s a biology teacher, he was particularly interested in that last one. When he realized there was a chapter on “heredity and eugenics” he of course had to start there. There were a few interesting highlights of this section. For example, like most people in 1946, the authors were pretty convinced that proteins were responsible for heredity. This wasn’t overly odd, since even the guy who discovered DNA thought proteins were the real workhorses of inheritance. Still, it was interesting to read such a wrong explanation for something we’ve been taught our whole lives.

Another interesting part was where they reminded readers that despite the focus on the father’s role in heredity, that there was scientific consensus that children also inherited traits from their mother. Thanks for the reassurance.

Then there was their descriptions of mental illness. It was interesting that some disorders (manic depressive, schizophrenia) were clearly being recognized and diagnosed in a way that was at least recognizable today, while others were not mentioned at all (autism). Then there were entire categories we’ve done away with, such as feeblemindedness, along with the “technical” definitions for terms like idiot and moron:

I have no idea how commonly those were used in real life, but it was an odd paragraph to read.

Of course this is the sort of thing that tends to make me reflective. What are we convinced of now that will look sloppy and crude in the year 2088?

If I understand correctly, we still know little of how things actually work in the brain. What makes ADHD? I suspect that in 2088 it won’t be overwhelmingly better.

Some psychoactive drugs seem to have different effects in different dosages, and effects change over time–it feels like doing percussive maintenance on a computer. “If you hit it here it seems to help sometimes. When it quits helping, hit it over there.”

I hope I’m not stepping on AVI’s toes here, but it wouldn’t surprise me if the received wisdom in 2088 weren’t along the lines of “That’s the brain. Don’t monkey with it.” Which might not always be better advice–some things seem to have helped, but the meds and dosages changed with time.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think it’s pretty guaranteed that something that seemed impossible will have been solved easily and something we thought we had down pat will turn out to be utterly wrong. Beyond that, I have no idea.

LikeLike

A good example of how everyday wisdom was better than the experts. People have been saying “she has her mother’s eyes/temper/voice” for hundreds of years.

I ran across that downward list of feeblemindedness in some of the oldest records when I started at the hospital in 1978, but it was already ridiculed then, as was the idea of mental age.

LikeLike

Interesting point about experts. It was hard to tell what they were actually refuting, but I suspect you are right.

Interesting that the feeblemindedness thing was at least somewhat used….

LikeLike

I remember reading the “feeblemindedness-moron et al” definitions. Now it is “developmentally delayed.” While it is correct that a “developmentally delayed” person is behind a normal person of that age, the term “delayed” usually implies there will be a catch-up. If spring is delayed some year- as seems to occur all too often in New England, we know that eventually spring will arrive completely,in all its glory.

By contrast, the “developmentally delayed” will never catch up. By adulthood, a “developmentally delayed” person may now be able to accomplish what a normal four year old can do. This would be a great advance from what the ‘developmentally delayed” could do at 4 years of age, but the “developmentally delayed” will never be able to do all that a normal adult can do.

Back in the day I worked as an aide in an institution for the mentally retarded. In our two week training session, we were informed that the mentally retarded at the institution were no longer to be called “patients,” but “residents.” The reasoning, our instructor told us, was that a “patient” usually recovers from an illness. For the mentally retarded at the institution, this was not the case. Their condition was permanent. As the mentally retarded lived at the institution, it was appropriate to call them “residents.” That made sense to me.

I later resigned from the institution for the mentally retarded to return to university. After I graduated, I went to work again at the institution to earn some money for a post-baccalaureate trip. In the one-day (re)orientation, I was informed that those residing at the institution for the mentally retarded were no longer to be called “residents.” Now they were to be called “clients.” That to me was a step too far, for three reasons.

My point of view is that a person who has clients is a college-educated professional. An aide, by virtue of not needing a college education to function on the job, is not a professional. Though sometimes customer is equated with client, and one needn’t be a professional to have customers. So, this is not the strongest of objections.

Second, if I am a client I have the capability to choose that professional or non-professional person.The mentally retarded at that institution had no choice in deciding that they would be my “clients.”

As a client, I am also able to articulate what I want accomplished for me- though I may be initially mistaken in what actually can and should be done for me. The mentally retarded at that institution had severe deficits in articulating their wants.

You can change the terms all you want, but you can’t as easily change the conditions the terms are supposed to describe.

LikeLike

Yes, many of the definitions were much cruder than what we use today. For example, “manic-depressive” has been replaced by bipolar, and it was described as someone who alternated between energetic criminality and being suicidal. Not how we’d describe it today, but you at least suspected they were talking about something similar.

Interestingly they had a lot of moral statements in their descriptions, whereas today our descriptors are (mostly) morally neutral.

LikeLike

I also thought it odd that the textbook would consider that an ongoing 15% of the population to not be normal, but only look so. Quite a revealing statement.

LikeLike

It gets a little creepy when you realize it’s in a chapter with “eugenics” in the title.

LikeLike