There’s a report that’s been floating around this week called Hidden Tribes: A Study of America’s Polarized Landscape. Based on a survey of about 8,000 people, the aim was to cluster people in to different political groups, then figure out what the differences between them were.

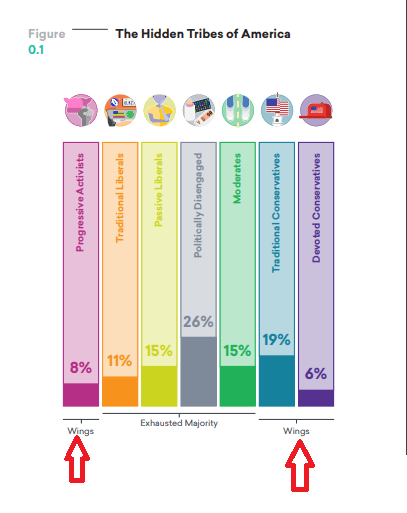

There are many interesting things in this report and others have taken those on, but the one thing that piqued my interest was the way they categorized the groups as either “wings” of the party or the “exhausted majority”. Take a look:

It’s rather striking that traditional liberals are considered part of the “exhausted majority” whereas traditional conservatives are considered part of the “wings”.

Reading the report, it seemed they made this categorization because the traditional liberals were more likely to want to compromise and to say that they wanted the country to heal.

I had two thoughts about this:

- The poll was conducted in December 2017 and January 2018, so well in to the Trump presidency. Is the opinion of the “traditionalist” group on either side swayed by who’s in charge? Were traditional liberals as likely to say they wanted to compromise when Obama was president?

- How do you measure desire to compromise anyway?

It was that second question that fascinated me. Compromise seems like one of those things that it’s easy to aspire to, but harder to actually do. After all, compromise inherently means giving up something you actually want, which is not something we do naturally. Almost everyone who has ever lived in a household/shared a workplace with others has had to compromise at some point, and two things become quickly evident:

- The more strongly you feel about something, the harder it is to compromise

- Many compromises end with at least some unhappiness

- Many people put stipulations on their compromising up front…like “I’ll compromise with him once he stops being so unfair”

That last quote is a real thing a coworker said to me last week about another coworker.

Anyway, given our fraught relationship with compromise, I was curious how you’d design a study that would actually test people’s willingness to compromise politically rather than just asking them if it’s generically important. I’m thinking you could design a survey that would give people a list of solutions/resolutions to political issues, then have them rank how acceptable they found each solution. A few things you’d have to pay attention to:

- People from both sides of the aisle would have to give input in to possible options/compromises, obviously.

- You’d have to pick issues with a clear gradient of solutions. For example, the recent Brett Kavanaugh nomination would not work to ask people about because there were only two outcomes. Topics like “climate change” or “immigration” would probably work well.

- The range of possibilities would have to be thought through. As it stands today, most of how we address issues already are compromises. For example, I know plenty of people who think we have entirely too much regulation on emissions/energy already, and I know people who think we have too little. We’d have to decide if we were compromising based on the far ends of the spectrum or the current state of affairs. At a minimum, I’d think you’d have to include a “here’s where we are today” disclaimer on every question.

- You’d have to pick issues with no known legal barrier to implementation. Gun control is a polarizing topic, but the Second Amendment does give a natural barrier to many solutions. I feel like once you get in to solutions like “repeal the second amendment” the data could get messy.

As I pondered this further, it occurred to me that the wings of the parties may actually be the most useful people in writing a survey like this. Since most “wing” type folks actually pride themselves on being unwilling to compromise, they’d probably be pretty clear sighted about what the possible compromises were and how to rank them.

Anyway, I think it would be an interesting survey, and not because I’m trying to disprove the original survey’s data. In the current political climate we’re so often encourage to pick a binary stance (for this, against that) that considering what range of options we’d be willing to accept might be an interesting framing for political discussions. We may even wind up with new political orientations called “flexible liberals/conservatives”. Or maybe I just want a good excuse to write a fun survey.

#3 is indeed fascinating. What if we as a society have already compromised? There was once a different status quo than there is now. We moved from there to here. That is usually a conservative-to-liberal movement, because “conserving” something usually means keeping it in a traditional way. (I get it that one can find examples, actual or theoretical, of a liberal status quo that is being moved in a conservative direction. I’m just sticking with the most common situation here for simplicity’s sake.)

In that instance, a conservative might say “Compromise? We have been compromising in one direction for the last eighty years! The ratchet never goes the other way. I refuse to compromise any further.” It would make the abstract Willingness to Compromise hard to measure. Similarly, if there is a dispute where the ratchet does always operate in one direction, however we classify it politically, the desire of one group to compromise is going to be necessarily much higher, because they know they can come back for more next year and try for additional concessions.

Tough to measure indeed.

Interesting that you went with this topic. I have already started a post on fanaticism this afternoon, which is a similar topic from a different angle. Your post here is already influencing mine.

LikeLike

Agreed. That’s why I think an issue like immigration might be a good measure of this, because there are two clear extremes (closed borders vs open) and no clear historical trajectory between the two.

I had a situation at work recently that reminded me of this. I had been promised two employees dedicated to my department, and then the department I was supposed to take them from got restructured. Everyone agreed that due to other issues, the team I was supposed to get the two employees from couldn’t spare two, and I agreed to take one instead. When this came up in a more general meeting, someone new to the situation asked if I could compromise on this, and perhaps only take half an employee. I had to explain the history, and the whole “actually this is the compromise thing”. They backed off and were fine, but it was a good example of the importance of a shared baseline in assessing compromise.

LikeLike

There’s also the weird issue of insincere compromise, what one party hears as “theft” or similar in the guise of compromise. This usually comes from things that /have/ a clear gradient, but where a binary solution is desired by one of the parties. A contrived example:

A: I’d like to sleep with your wife every day after work.

B: No.

A: How about just Monday, Wednesday & Fridays?

B: No.

A: Ok, let’s compromise: I’ll only sleep with your wife on every other Tuesday. You don’t even get home until late on Tuesdays!

B: No.

A: Why are you being so stubborn???

To some who are otherwise willing to compromise on many things, some offers to “compromise” sound a lot like this sort of thing.

To further complicate things, not everyone is in agreement about “a binary solution is desirable”. A good example of that might be gun rights. The “no one needs any guns” folk, the “I should have access to whatever weaponry I want” folk and the “let’s talk about some common-sense limitations” folk all make strong arguments, and I don’t think we can declare one or the other of them “best” without introducing a lot of “because that’s what *I* think” into the mix.

To a “any gun I want” person, “how about just assault weapons, then?” sounds a lot like “how about just on Mon, Wed Fri…?”

Etc.

#itsComplicated…

LikeLike

That’s a good point. At times, asking to change the current state isn’t just upsetting the status quo so much as violating widely recognized boundaries.

Politically this comes in to play a lot when we discuss taxes. There are some people who start with “the money is mine, and the government better make a great case for every penny they want to take” and others who start with something closer to “we all have to chip in something, we’re just discussing details.” Very hard for those two perspectives to find any common ground, let alone compromise.

LikeLike

Pingback: Where is the Center? | graph paper diaries