Welcome back folks! Last week I started to introduce a new series on the relationship between the issues in true crime and the issues in scientific publishing that led to the replication crisis. I am going to start working through some of the proposed causes for the replication crisis in science, and connecting them to similar issues in true crime. I’m going through these in the order the Wikipedia page on the replication crisis, and today we start off with some big picture stuff: historic and sociologic causes. So what did we see in science?

Scientific Senility, Overflow Theory, and the Enemies of Quality Control

The first thing that caught my eye is that the replication crisis in science was predicted all the way back in 1963 by a man named Derek de Solla Price, who might have been one of the first scientists to study, well, science itself. Solla Price became alarmed at the exponential growth of scientific publication and the inability of science itself to police a body of knowledge that was doubling every 10-15 years. Indeed, we see that the amount of money sunk in to scientific research has jumped over the years:

He was afraid the science would reach the point of “senility” after it saturated, where further findings were simply nonsensical. He also grew concerned that increased participation in science would not inherently mean more of the best and brightest would enter science, but rather that the best scientists would get bogged down working in a competitive field and the quality of your average scientist would decrease.

These predictions seem prescient, as decades later scientists are indeed bemoaning scientific “overflow“, or the phenomena when the “quantity of new data exceeds the field’s ability to process it appropriately”. Additionally, it’s been noted repeatedly that the huge influx of money in to science meant that doing research that got funding was as important as doing good research.

Finally, they wrap up by noting that science was subject to three forces that can compromise the ability to prioritize quality control on any topic: mediatization, commodification and politicization. All of those factors have only increased the competing forces in science, and made it all the harder for people to focus on the original purpose.

So How Does This Apply to True Crime?

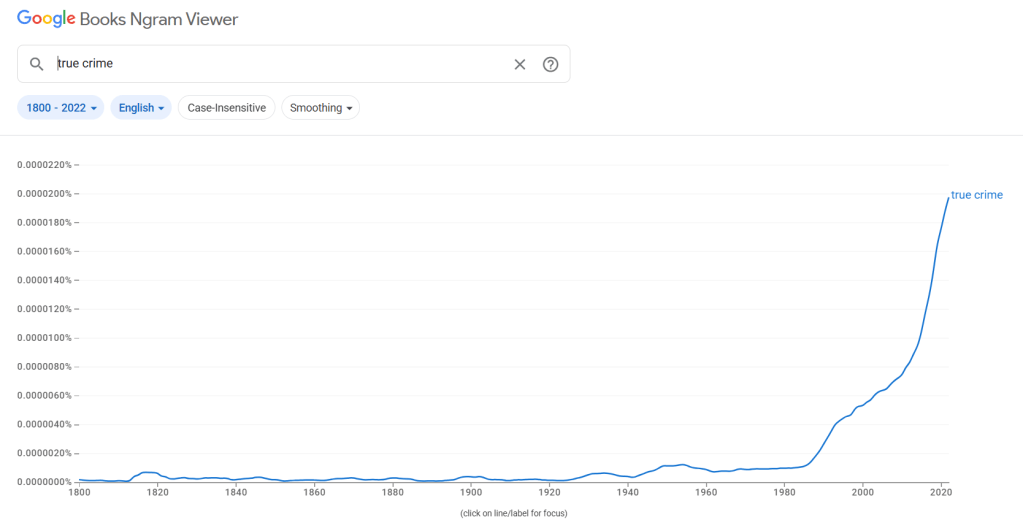

The exponential growth of science has been almost nothing in comparison to the exponential growth of true crime content. Google ngram has an interesting visual of the number of times the phrase “true crime” has been mentioned in books over the years:

Yup, looks like exponential growth to me! Additionally we know that the number of true crime podcast listeners has tripled in the last five years (6.7M (2019) to 19.1M (2024), and that true crime content is fueling the documentary boom on streaming services (6 of the top 20 in 2020, 15 of the top 20 in 2024). Now if science, whose stated goal is to aim for truth with a pre-existing system of peer review to screen work, can’t handle keeping up with the enormous influx of new information, how is true crime supposed to keep track of it’s quality while pumping out new content? After all, with science you still have multiple barriers to entry (education, institutional affiliation, etc) and a set format for your work. With true crime, literally anyone can hook up a microphone and start a Tiktok or podcast, and the stated goal is often story telling, with truth as a secondary aim.

This also suggests that de Solla Price’s concern about a massive influx of scientists degrading the average quality also has some applicability to the true crime space. While there are many well credentialed and thoughtful true crime content producers, they will always be competing with others who may be trying less ethical ways of getting attention. Indeed, as my town got flooded with true crime content producers, I was somewhat fascinated to look in to the backgrounds of some of these people. A surprising number of the smaller creators were people who literally could not hold regular jobs due to their own prior run ins with the law. Over the course of watching some of the feuds that started between them, I learned at least one podcast host had confessed in writing to others she’d ended up realizing a lot of the story being peddled was unsupported by evidence, but unfortunately she had a lot of debt and her podcast was now the most successful it had ever been so she couldn’t stop. She ended up pairing up with one of the biggest true crime podcasts going and gets 10s of thousands of views on Youtube, in case you’re curious. Trafficking in other people’s pain is big business.

While I point some of this out just because it annoys me, I am not sure many people are aware of how big this ecosystem has gotten. For every major Netflix documentary, there are thousands of TikTokers and Youtubers doing secondary reporting/commentary, and millions of people viewing their content. Learning all the facts of a lengthy and complicated case is probably just as hard as many scientific fields, and getting everything right takes an extraordinary amount of effort most people don’t have time for in the YouTube/Tiktok era. So we’re left with the three challenges mentioned above:

- Mediatization: “If it bleeds it leads” has been a truism in media since William Randolph Hearst popularized the phrase in the 1890s. When trying to capture eyeballs, you are going to have to make whatever you are saying entertaining. If scientists can be sucked in to overstating their own findings based on the siren call here, do you really think a documentary film makers are going to overcome this temptation? After all, science has it’s own hierarchy and prestige/awards, true crime is nothing without the media. It is media. Additionally, the media environment for true crime has changed recently from “those experienced enough to get a newspaper job or book deal” to “those who can host a podcast or Youtube channel”, which opened up the floodgates to anyone who wanted to jump in.

- Monetization: Most scientists have a base salary they are working with and then competing for grants, almost every true crime content creator is reliant on the popularity of their content for money. I made a personal rule not to listen to any content creator who doesn’t maintain a day job, otherwise bending to your audience is not just a temptation, but a financial necessity. Additionally, some of the top content creators have ended up making millions, so there’s a real upside here if you can get your content to hit well enough. Most scientists can only make that kind of money if they hit a blockbuster drug or something like that.

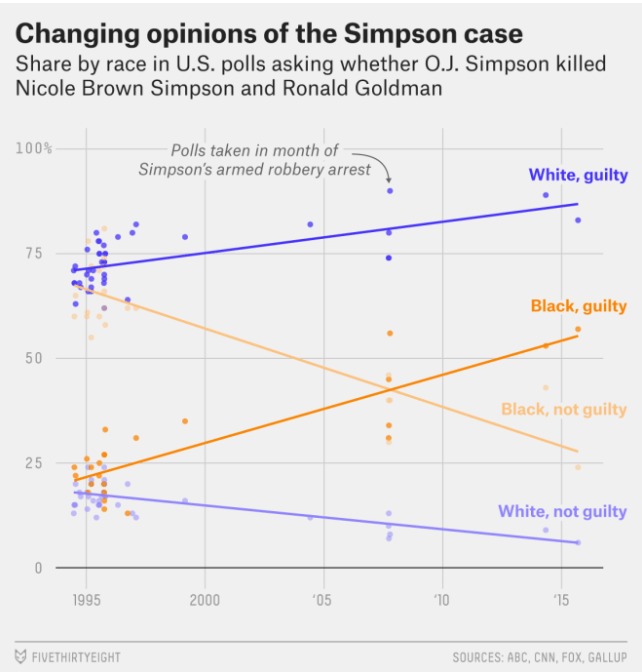

- Politicization: Just like science got sucked in to a lot of political fights, so has true crime. The most classic case of this might be OJ Simpson, where the case got massive play in part as a way of people expressing their racial anxiety. The impact of politics on this case can be seen clearly by the profound increase in people who believe OJ was guilty by year. As the political conditions changed, so did people’s assessment of the evidence:

While the OJ case is perhaps the clearest example of this, we also know that sensational crime tends to follow the anxieties of the age. Serial killers dropped as mass shootings increased. We may now be entering an era of political assassinations. Some of the true crime “truther” type movements seem to reflect a general distrust of “official” stories, as we see even suspects who plead guilty get rabid fanbases that maintain their innocence.

I think it’s safe to conclude that in both science and true crime, a large influx of participants, money and eyeballs combined with political anxieties have had an impact on the quality of content. Interestingly, I actually encounter more people currently who are willing to be skeptical of science than those who are willing to be skeptical of crime reporting. I think there’s a feeling that the average lay person can suss out a guilty person vs a not guilty person, but I’m not sure that’s true if you’re not hearing all the facts. Our assessment of stories and their truthfulness can often hinge on small details, so it’s important to note that all the same forces that acted on science are present in even larger amounts in true crime.

That’s all I have for now, in the next installment we’ll be looking at problems with the publishing system for both science and true crime.

To go straight to part 2, click here.

I was wondering how you were going to pull this off, but I see the connection: what happens when the barriers to truth and honesty come down, overrun by a stampede of popular demand? I am reminded of Luther’s statement that locks are for honest people. Thieves see them only as an inconvenience, but honest people take the reminder that there is a standard.

LikeLike

Exactly. And I’m surprised how many people simply don’t see the risk here, handing our justice system over to whoever tells the story they like the most.

Yes, the other people being dragged in to these things are mostly not being prosecuted by the state, but to be accused of murder by any large group of people seems like it would have a pretty substantial impact on your life. That’s not something I think we should be taking lightly.

LikeLike