Well hi there! Ben and Bethany here, and we’re counting down the top science references in popular music. Last week we went over the rules and introduced Ben, so go check that out first if you’re at all confused. We’re going to start off the rankings nice and slow, beginning with 10 songs that get science right. These are the good guys.

“Sounds of Science” by the Beastie Boys

Nominated Line: “Dropping Science like Galileo dropped the orange” (3:08 mark)

Bethany: Ooh, we’re starting off with a good one here. Can I just say I love this line? And not just because Neil Degrasse Tyson uses it in his show intro for Star Talk. No, I love it because 1. the reference is not the obvious fruit based scientist one* and 2. it’s being used accurately and describes something not quite intuitive. The reference here is to the Leaning Tower of Pisa experiment. While the details are probably apocryphal, the legend goes that Galileo went to the top of the Leaning Tower of Pisa, dropped an orange and a grape off the side, and used it to prove that gravity was not dependent on the mass of the object. Nice high school physics callback there.

*I mean, good job on the gravity thing and all Newton, but you’re getting a little cliche don’t you think?

Ben: Bethany, thanks again for having me. This is basically everything I like to do, put together in one blog post, and the best part is I get to hand off all the tricky research parts of it to someone much more qualified than me. I’m not even certain what my Google search history would look like if I were in charge of both jobs, but my first search would probably be, “what IS science?” and that’s probably a rough place to start.

“Sounds of Science” is a collection of everything I like about the Beastie Boys – showboating rapping, frenetic changes of pace, ludicrous levels of hyperbole. They make sure to brag about their prowess in… every possible context, compare themselves to Jesus Christ, then sing a Simon and Garfunkle chorus on top of a Beatles sample. They don’t lack for confidence.

As for the science, all of it seems fair – after all, “with my nose I knows and with my scopes I scope” is certainly factually accurate. I’m glad Bethany’s here, though, because I could use an explanation of what, exactly, “the radium, EMD squared” means.

Bethany: Well in addition to rhyming with “Shea Stadium”, the radium thing appears to be an incredibly clever reference. Paul’s Boutique, the album this song was on, came out in mid-1989. We can assume most of the songs on it were written or recorded in 1988, and the atomic number of radium is…..88. Thank God they didn’t record it earlier or later, because Francium and Actinium just don’t roll of the tongue quite as well.

Based on my research, the EMD squared thing actually should have been your wheelhouse. EMD was the distribution arm of Capitol Records, their label. The squared part of course is a reference to Einstein’s mass/energy equivalence formula.

Ben: That’s a pretty classic Beastie Boys move – it’s clever, it scans, it’s a little sloppy and doesn’t quite fit – but you can’t stop and look at it too closely, because by then the boys are three verses ahead of you.

“We Didn’t Start the Fire” by Billy Joel

Nominated line: Multiple mentions but I like “children of thalidomide” (1:50 mark)

Bethany: How do you pick a reference out of a song that is literally all references? Arbitrarily, that’s how. Actually, this isn’t totally arbitrary. Joel’s song here is an anthem covering lots of major world shaping events, and I actually really appreciated him throwing a medical reference. Thalidomide was a drug given as a sedative that was also prescribed to pregnant women for morning sickness. Despite assurances from the company that it was “completely safe” it was actually quite dangerous and resulted in children with deformities…most notably limbs that never grew and a 50% mortality rate. It’s an incredibly depressing story, but it helped push forward drug regulation and the role of the FDA in monitoring drug development. I give Joel full credit here for recognizing the importance of this historic event.

Ben: Well, this is a bummer. I hadn’t known any of this.

You wouldn’t know how dark the lyrics are from listening to the song. I’d always been aware that “We Didn’t Start the Fire” was supposed to be a protest song, but actually experiencing the song means listening to an aggressively upbeat number that is supposed to ironically contrast with the song’s content, but mostly just turns it into a catchy can-you-sing-along? contest.

As I think will become a continual theme for my responses, I highly recommend watching the entire music video, if only for the surreal moment of watching Billy Joel play an imaginary pair of bongos in front of a flaming picture of the execution of Nguyễn Văn Lém. In fact, Joel is playing imaginary bongos a fair bit during this song, as I guess that’s his go-to motion when he gets nervous. I get you, bro.

“Affirmative Action” by Foxy Brown

Nominated line: “32 grams raw, chop it in half, get 16, double it times three/We got 48, which mean a whole lot of cream/Divide the profit by four, subtract it by eight/We back to 16.” (3:34 mark)

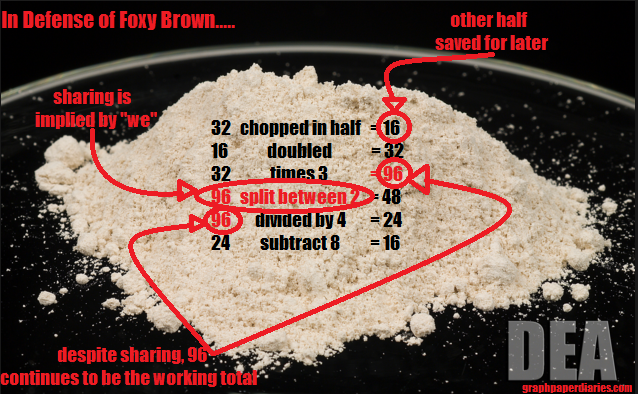

Bethany: Ms Brown’s lyrics have caused quite a stir, and got her voted the all time 5th worst rap line of all time by About.com. This line reminds me of one of those stupid Facebook math problems where someone makes an equation purposefully unclear then everyone argues over order of operations like that’s a thing we really all care about. However, let it never be said that I’m not willing to take sides in an argument I find stupid. Thus, here you go:

The only slight ding I give her is changing units half way through the problem, from grams to profits.

Ben: I like how you used an actual DEA photograph of heroin for the picture. Make sure everyone knows you didn’t just have that lying around.

I think Ms. Brown is significantly mistreated for her honesty in this song. This is actually not a Foxy Brown song, but a Nas song featuring remaining members of “The Firm” (AZ, Cormega, Brown), bragging about their heroin and coke-dealing exploits. The first three rappers spend their verses explaining what kind of cars they’ve purchased, except for Nas, who seems to have a bit of a death wish and spends half his verse on the reality of response killings.

It’s clear that Ms. Brown is in charge of the day-to-day business operations, and if she’s got to cut into the purity of her product in order to make a profit, that’s something she’s willing to do. She’s a business, man. And she doesn’t mind telling you how she goes about it.

Though it does seem like it would cut into any future profits to admit that you’re not giving out top-of-the-line material. This song is basically “The Big Short,” but for drug dealing.

Bethany: Reading your explanation makes me remember all the math problems I did in high school where they irritated me by adding superfluous words to “challenge” us. I DON’T CARE WHY SUZY AND JOHNNY WANT ORANGES JUST GIVE ME THE NUMBERS.

Ben: I was always the opposite, I wanted more backstory. WHAT’S GOING TO HAPPEN WHEN THE TRAINS PASS? IS THERE SOMETHING WRONG WITH THE TRACKS? HOW MUCH TIME DO WE HAVE BEFORE THIS WHOLE THING IS BLOWN TO HELL? *furious hacking motion on imaginary keyboard* GET OUTTA THERE, JIMMY, YOU’RE NOT NOT GONNA MAKE IT!

“Why Does the Sun Shine?” by They Might Be Giants

Nominated Lyric: Whole Song

Bethany: They Might Be Giants has a whole album of kids songs called “Here Comes Science” and this is one of the most popular songs off that album. While it plays slightly fast and loose with describing the exact composition of the sun, they retain full credit because they wrote their own rebuttal song clarifying where they’d simplified things. That actually puts them ahead of at least 30% of practicing scientists.

Ben: Guys. Guys. I learned so much from this song. Copper can be a gas?

History of Everything (Big Bang Theory theme song) by Barenaked Ladies

Nominated line: Whole Song

Bethany: If you’re a science geek, hold Sheldon Cooper up as a hero, and have an hour or two to kill, go read this post and thread to get excruciating detail on how accurate this song is. For everyone else, don’t cite it in your PhD thesis, but it’s actually pretty close. Plus, it’s popular and admire any band that can make a song with that level of detail catch on.

Ben: To all the Barenaked Ladies haters out there, you should know that I’m basically these people whenever someone takes any shots at BNL.

I’d never actually listened to the entire song before, just the short bit that plays before “Big Bang Theory” episodes, and I enjoyed yet again learning things. Our universe is going to start contracting? Guys, I have not been paying attention to anything. My mind was blown before Kevin Hearn* had even started his keyboard solo.

*Yes, I do know the name of Barenaked Ladies’ keyboardist. Don’t step to me.

Bringing up BNL actually brings up some me-and-Bethany ties, because when I was in 8th grade, my dad took me and her younger brother Tim to a massive outdoor festival in downtown Boston, dropped us off, and arranged to meet us in about 8 hours* at a Dunkin Donuts about a mile away. This was before the age of cell phones. I have literally no idea what would have happened if we hadn’t shown up. Bethany was justifiably furious, as she had been denied going to go see Ani DiFranco earlier that month with friends, and she was a high school junior at the time.

* It was a long concert. The show’s lineup was: The Corrs, Edwin McCain, Sister Hazel, BNL, and Hootie and the Blowfish. My first concert was the most 90’s concert of all time.

Bethany: Thanks for reminding me of this incident. I haven’t harassed my parents about this injustice in years. They’re due for another round. Also, Barenaked Ladies haters only exist in highly controlled lab experiments, not in the wild.

Ben: Oh, phew. I’ll put my Internet Comment Gun back in its holster, then.

In the least shocking development ever, we appear to be going a bit long here. The next 5 songs will be split off into Part 2, going up next week. Don’t wait until then to complain to us about what we missed, feel free to start now.