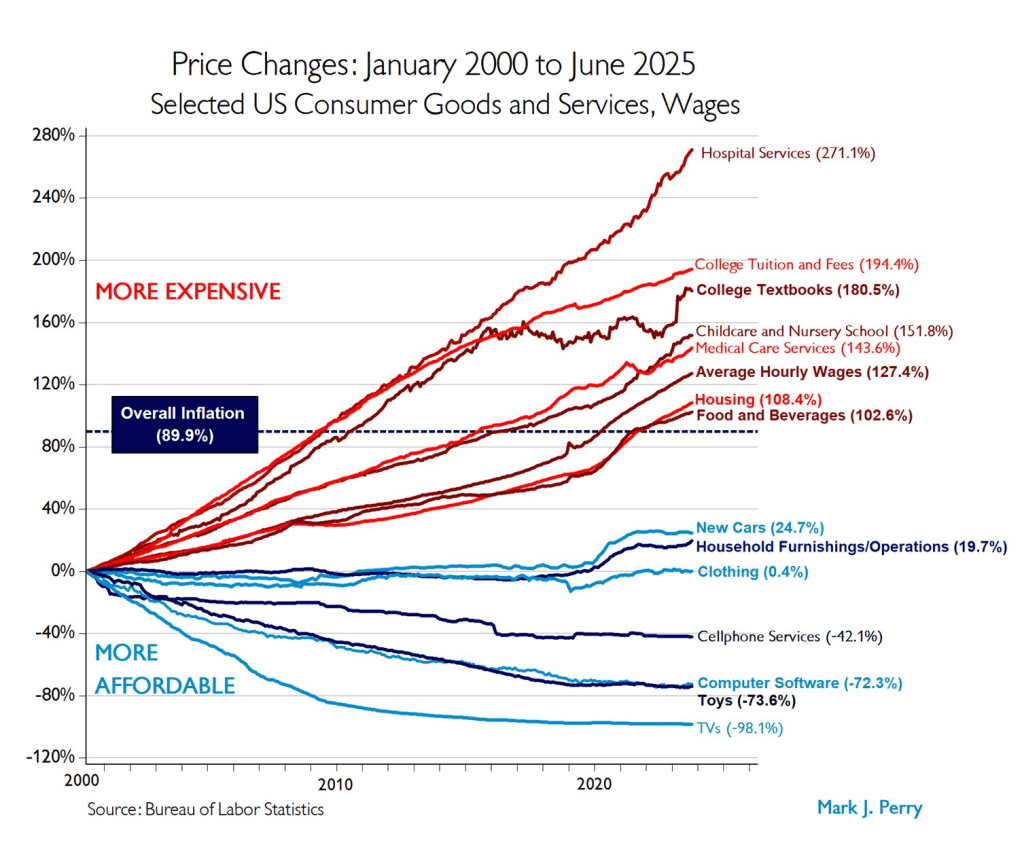

When it comes to current day financial woes, it is common to hear people focus on three things specifically: housing, higher education and health care costs. This will often be accompanied by something like Mark Perry’s “chart of the century” that shows the increase in prices vs wage increase since the year 2000:

Of the 5 categories of spending that outpaced average wage growth, 2 are in healthcare. But those healthcare categories are much trickier than the remaining 3 categories. If I bring up childcare spending, college textbooks or even college tuition and fees, you pretty much know what that covers. Even if you haven’t personally used it in a while, you probably know what a daycare or bachelors degree entails, and I think we all have the same memories of college textbooks. But how do you compare the cost of healthcare in the year 2000 to today? What are we even comparing when we say “hospital services”? How do we add in the fact that there is simply more healthcare available now than there was 25 years ago?

As it turns out, this is an incredibly tricky problem no one has quite solved. The data above comes from the BLS medical CPI data, which tracks out of pocket spending for medical services. It states that in general “The CPI measures inflation by tracking retail prices of a good or service of a constant quality and quantity over time.” But as someone who has worked in various health care facilities since just about the year 2000, I am telling you no one actually wants to revert back to the care they got then. Additionally, CPI tracks the price of something, but not how often you need it or why you needed it.

Here’s an example: when I started in oncology, all bone marrow transplants were done inpatient. Then, people started experimenting with some lower risk patients actually getting their transplants outpatient. People really love this! They sleep in hotel rooms with more comfortable beds, and walk in to clinic every day to get checked up on. However, this means that your average inpatient transplant is now more complex, the “easy” patients who were likely to have a straightforward course of care were removed from the sample. I don’t often look at what we charge, but I wouldn’t be surprised to see that the cost for an admission for bone marrow transplant has continued to trend upward. But this doesn’t mean the cost has actually gone up for most patients. In this case, comparing the exact same hospital stay for the exact same diagnosis as 25 years ago is not comparing the same thing. Innovation didn’t change that some patients need a hospital stay, it meant that fewer patients needed one.

While this is one example, I suspect rather heavily that’s a big reason why hospital services cost has gone up so much. The big push in the last 2 decades has been all about keeping people out of the hospital unless they really need to be there, which will have the effect of making hospital stays more expensive while keeping more people out of the hospital.

This run off can also increase the cost for outpatient medical services, the other category we see above. This past year for example, I got my gallbladder removed. In the year 2024, 85% of people who got a gallbladder removed went home the same day, as did I. In the year 2000 however, that was hovering at around 30%. So again, we see that the hospitals are now caring for just the sickest people, but one also assumes that outpatient follow up visits might be more complex than they were 25 years ago. Having 50% of patients change treatment strategies is a huge shift in the way care is delivered, even if it shows up as “the exact same visit type for the exact same diagnosis”. From the standpoint of CPI, a ‘gallbladder removal’ looks like the same service. From the standpoint of reality, it has become a fundamentally different care pathway.

Now this is just one graph, and it’s true there are other graphs that get passed around that show an explosion in overall healthcare spending. This is also true, but fails to reflect that the amount of healthcare available since <pick your year> has also exploded. Here’s a list of commonly used medical interventions that didn’t exist in the year 2000:

- Most popular and expensive migraine drugs (CGRP inhibitors)

- GLP 1s for diabetes/weight loss (huge uptick in the past 5 years)

- Cancer care (CAR-T cell therapy and immune checkpoint inhibitors)

- Surgical improvements (cardiac, joint replacement, etc)

- Cystic fibrosis treatment (life expectancy has gone from 26 to 66 since 2008)

- HIV treatment (life expectancy was 50-60 in 2000, now is the same as the rest of the population)

- ADHD medication (this one is more an expansion in diagnosis, was $758 million in 2000, now estimated at $10 to $12 billion. I bring this up as a tangential rant because for some reason I’ve seen 2 people recently mention that insurance annoyed them because they didn’t use it because they were healthy, but they or their children were on ADHD medication. If you are going to complain about healthcare costs, it’s good to make sure you are accurately assessing your own first.)

Childcare or higher education have made no similar changes in the same time period.

My point here is not that healthcare has no inflation, it almost certainly does. Rising wages, increased IT needs, increased regulatory burden and increased cost of supplies would all hit healthcare as well. But when you compare healthcare in the year 2000 and the year 2025, you are comparing two different products. Go further back with your comparison and the differences will be even more stark. We are never going to control healthcare costs as long as we are constantly adding new, cool and really desirable things to the basket. There is not a world in which we can both functionally cure cystic fibrosis AND do it for the same price as not curing cystic fibrosis. Not all cost increases are the same.

There’s a similar story with college textbooks, and partially so with college tuition and fees. As an example, I teach an introductory master’s level course in computer science every semester (my “side hustle”). The textbook, a very standard one for this course, is $150 list price. I’m nearly certain that I’m the only one who actually bought one though! The students have an e-version from the library for free, and I tell them to use that; if they really must have a paper book to study (hey, there are still some people like that out there!), I tell them to either rent it on line (usually $30 or so for the semester) or get a used copy (typically $50-70, depending on how fussy you are about somebody else’s highlighting, and you get about half that back at the end if you re-sell it). Used books have been around forever, of course, but textbook rentals weren’t a “thing” in 2000 for sure. For college tuition, almost all of our students are getting their classes paid for by their employers, so students don’t foot the bill for much of at least this program. (There are standing tuition agreements with some major employers, who don’t pay list price for sure.) There is also a very significant push-back on overall cost now (which didn’t exist in 2000), and a number of new entrants into the field who are aggressively undercutting the established players (e.g. my own program). Even if you are paying full freight, you aren’t paying for food, housing, campus amenities, etc., resulting in a degree that is about half the cost of going in person… but the diploma still says “Big Name U” on the top. So, the “easy” students and subjects to teach, are being pulled off to lower cost, lower “touch” programs online, leaving either the harder to teach students or the must-be-in-person subjects (hands-on labs, for example) to bear all of the sunk costs of the campus.

LikeLike

Excellent points and a great perspective!

It reminds me of a similar discussion around public schools vs charter schools in my area, and why charter schools were able to educate kids for a lower cost. The public schools pointed out that charter schools wouldn’t take the most labor intensive students: those with any sort of learning disability, behavior problem or who had English as a second language. This meant the public schools were now left with the more challenging kids, and so their average cost per student kept going up.

Interesting stuff.

LikeLike

Thanks for this article, and for highlighting why it is so hard to understand what costs are really doing.

I receive an intravenous medical treatment for three days every six weeks. For years I went to an outpatient hospital clinic for the infusion. When in-home infusion became available about three years ago, I asked my doctor if he could arrange that, instead. It was not an easy process, but it finally got approved by my insurance company, even though having it done in my home is less expensive for them. I’m not sure why they were so reluctant, except that maybe they are afraid of liability issues if something went wrong, and I was not right there in the hospital to be treated. But I had a history of about 12 years of treatment at the hospital, with no problems whatsoever. The in-home infusion is MUCH more comfortable, and I continue to have no problems. If we want to keep costs down, we need to learn to be flexible with new approaches like this.

LikeLike

Great example! I don’t deal with insurance for my job, but I sit in on a lot of conversations where it’s discussed. My bet for your case would be the insurance company didn’t have a contract with the people who do the in home infusions or there was some other payment issue. We see that a lot when new options become available, and we still have some insurance companies that won’t let us get certain common tests done at local doctors offices because they want to just send one payment to the hospital for everything. Its maddening!

I completely agree we have to be flexible to lower costs. Any option that patients like more and that is cheaper should be the first priority!

LikeLike

Your paternal grandmother was in the hospital for about 2 weeks after having her gall bladder out in 1962. Also, another well done post!

LikeLike

Oh man, while I was recovering from my surgery I flipped on an episode of the Golden Girls where one was listing all the things she did for her ex husband, like “spending a month by your side in the hospital after your gallbladder surgery”. You’d have to be extraordinarily sick to get that kind of time inpatient now.

Laparoscopic surgery was pioneered prior to the year 2000 so I didn’t mention it here, but it did wonders for healing time and hospital stays.

LikeLike

Very similar for psychiatric care, and families were not always happy to see their relative get out quicker, with psychosis still present but diminishing. Outpatient care became increasinging important and complicated. I have said for years that health costs have soared because they can now do magic, and any D&D player knows magic is expensive to purchase. My examples have been for much longer timelines, like a century, because I don’t really know as much about the last 25 years. But in 1925 there were no antibiotics. They could tell you your heart wasn’t good enough to go into the army but they couldn’t do much about it. They could tell you it looked like cancer and what your life expectancy was. They could put a sign on your house that you were quarantined, and even that was new. They could set a bone or give you something that sorta worked for constipation of diarrhea. Mostly, you just died or had some permanent condition.

LikeLike

Great examples. I didn’t add it because it’s ultra new, but we can now cure sickle cell disease for about $3-4 million a pop. Wildly expensive but if you’ve ever seen a sickle cell crisis you’d much rather live in a world with any treatment than nothing at all.

LikeLike

We recently watched a bunch of somewhat old British detective series on TV, maybe from 15-25 years old. I was struck by how many characters had heart attacks and seemingly got some bed rest, then were sent home. Often the plot turned on their dropping dead not long after.

LikeLike

TV shows tend to lag with their medical knowledge, but I just looked it up and the chances of dying from a heart attack actually did cut in half between 1999 and 2020: https://www.acc.org/About-ACC/Press-Releases/2023/02/22/21/30/Heart-Attack-Deaths-Drop-Over-Past-Two-Decades

LikeLike

First, I do not disagree with anything you’ve written. There have been amazing advances in medicine — I’ve witnessed them. Second, I wonder how much it matters in day-to-day hospital care now. Of course, I am basing this on my own experiences caring for a severely injured child, my parents, and husband all within hospitals and outpatient settings over 40 years. That also included dealing with insurance.

I’ve been hospitalized 3 times in the past 7 years, and each one has left me with a “never again” feeling and relief that I escaped. Also, I moved from a city which had a medical school and a few competing hospital ‘chains’. But whoa… the facilities here are bare bones. And by bare bones, I mean the beds, gurneys, and other facilities for basic human care – 3″ of cheap foam padding is considered a luxury.

I am not talking about the care from nurses, but about the fact that the hospitals no longer provide them with the basics to adequately care for their patients. They do have great computers on rolling stands… while the length of IV tubing does not allow their patients to get out of bed.

Thus, I do not think the increased cost of hospital care is justified.

Some of the insurance struggles over the years have been “interesting”. When my son was injured, I had (through my employer) one of the first HMO plans and we had no out of pocket costs, but limited choice of providers. Had it not been that we were in a location where Scottish Rite Hospitals was available to us… who knows? At that time, Scottish Rite and Shriner’s hospitals did not take advantage of subrogation, thus my HMO sort of got off “scott free”. Not only that, my husband’s coverage through his employer was not tapped.

Nor am I complaining now about my insurance coverage. I’m still “over-insured” at minimal cost (due to military service) and so very grateful for it. That doesn’t mean I think hospitals are offering great care for what they’re charging. Nor does it mean that I think the increase in hospital costs are entirely due to the availability of advancements in medical treatments.

LikeLike

These are great perspectives, thank you! A lot of what your saying here actually hits at the core of my day job, so I’ve devoted an absolutely enormous amount of my professional life to these issues and thus am also called on a lot in my personal life. After 20+ years of that, I also avoid hospitalizations at all cost. They’re pretty miserable even in the best of circumstances…there’s a good reason lots of transplant patients would rather spend the night in a hotel and walk to clinic every day rather than get admitted, and they’re literally getting a life saving procedure. So I don’t think your impression is wrong at all.

That being said, a few other points spring to mind. First, hospitals definitely do cut corners, some more than others. About half of all rural hospitals are under water financially and about a third of urban hospitals, so the financial pressures are enormous. The first things to go are often the things patients like the most, but if it’s not going to literally kill you it can often get chopped. I am absolutely not minimizing how patients feel here, but sometimes the bed/gurney budget went to something unglamorous like the HVAC system. Again, I will fully admit some of these decisions are penny-wise/pound-foolish, but sometimes they really were just someone doing the best they could with limited funds.

Second, you mentioned caring nurses, so it might be of interest to you that nurses are the single biggest line item in a hospital budget, comprising about 30% of the total in most hospitals: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21799362/

One of the points I was trying to make in my post is that your average inpatient is a lot sicker now than they were in decades prior, which means the nurses have to be even better trained and thus command higher salaries. My grandmother was a nurse back in the 1940s and 50s, and the job she described doing seemed downright easy compared to my mothers (also a nurse) in the 70s and 80s which pales in comparison to what my sister (yet another nurse!) had to do in 2010s. I believe nurses deserve the money they get, but as long as they command higher salaries, they cuts have to come from somewhere else. The caring nurse/short on equipment dichotomy you described is in part driven by this dynamic.

All that being said I can absolutely see how costs would get higher while people would feel they were getting a worse experience. An improvement in a surgical procedure doesn’t look much different for a patient who’s knocked out during the whole thing, but the other cuts will be very apparent. No one who lives through a heart attack knows that they would have been the one to die back in 1999, so they ironically see more of the flaws of the hospital than they would have otherwise.

Either way I doubt this problem is going to improve any time soon, although at least in my little corner of the world we work on it constantly.

LikeLike