This week I was rather surprised to find out that a early-20s acquaintance of mine who lives in a rather rural area did not have a driver’s license. I know this person well enough to know there is no medical reason for this, and she is now pursuing getting one. Knowing the area she lives in I was pretty surprised to hear this, particularly considering she has a job and a small child.

Now living around a large city with lots of public transportation options, I do know people who are medically unable to get a license (and thus stick close to public transit) and those who simply dislike the thought of driving (because they grew up around public transit), but I hadn’t met many people in the (non-big city) area I grew up in who didn’t get a license.

As often happens when I’m surprised by something, I decided to go ahead and look up some numbers to see how warranted my surprise was. It turns out I was right to be surprised, but there may be a trend developing here.

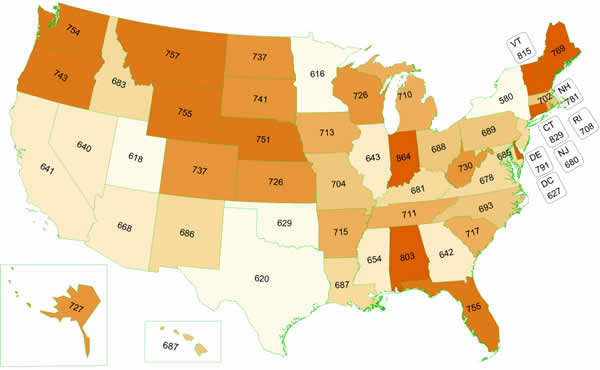

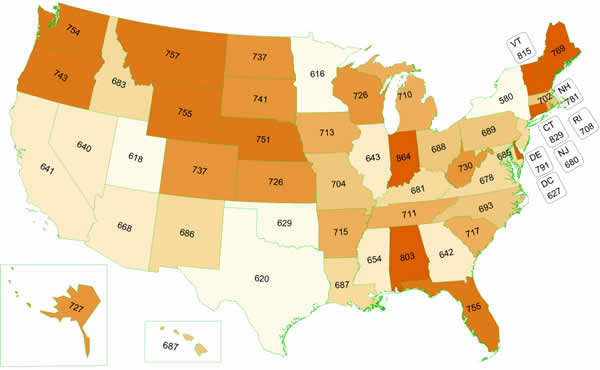

According to the Federal Highway Administration, in 2009 87% of the over-16 population had a driver’s license. There’s a lot of state to state variation, but the states I’ve lived in do trend high when it comes to the number of drivers per 1000 people:

Note: that map is licenses per 1000 people of all ages, so some states with particularly young populations may get skewed.

This appeared to confirm my suspicions that not having a license was relatively unusual, particularly in the New England region. Most of the places that have lower rates of licenses are those that have big cities, where presumably people can still get around even if they don’t know how to drive. I am a little curious about what’s driving the lowish rates in Utah, Texas and Oklahoma, so if anyone from there wants to weigh in I’d appreciate it.

I thought that was the end of the story, until I did some more Googling and found this story from the Atlantic, about the decreasing number of people who are getting driver’s licenses. The data I cited above is from 2009, and apparently the number of licensed drivers has been falling ever since then. For example, this paper found that in 2008, 82% of 20-24 year olds had driver’s licenses, but by 2014 76.7% did. In contrast, in 1983 that number was 91.8%.

So what’s the reason for the decline? According to this survey, the top 5 reasons for those aged 18 to 39 are “(1) too busy or not enough time to get a driver’s license (37%), (2) owning and maintaining a vehicle is too expensive (32%), (3) able to get transportation from others (31%), (4) prefer to bike or walk (22%), (5) prefer to use public transportation (17%)”.

Like most surveys though, I don’t think this tells the whole story. For example, the top reason for not having a license is that people are “too busy” to get one, but the study authors noted that those without licenses are less likely to be employed and have less education than those with licenses. This suggests that it is not extended outside commitments that are preventing people from getting licenses. Additionally, anyone who has ever lost the use of their car knows it can take a lot more time to get a ride from someone else than it does just to hop in your own vehicle.

My personal theory is that getting a drivers license is something that requires a bit of activation energy to get going. Over the last decade or two, state legislatures have progressively enacted laws that put more restrictions on teen drivers, so the excitement of “got my license this morning and now I’m taking all my friends out for a ride tonight” no longer exists in many states. For example, in Massachusetts drivers under 18 can’t drive anyone else under 18 (except siblings) for the first 6 months. This is probably a good practice, but it almost certainly decreases the motivation of some kids to go through all the work of getting their license. After all, this is an age group pretty notorious for being driven by instant gratification.

Additionally, with high costs for insurance and vehicles, many parents may not be as excited for their kids to get their license. Without parental support, it can be really hard to navigate the whole process, and if a parent starts to think it may be easier to keep driving you than to pay for insurance, this could further decrease the numbers. With younger generations spending more time living at home, parental support is an increasing factor. Anyone attempting to get a license has a certain reliance on the willingness of others to teach them to drive and help them practice, so the “too busy” reason may actually be driven just as much by the business of those around you as your own business. You can be unemployed and have plenty of time to practice driving, but if no one around you has time to take you out, it won’t help.

Finally, there may be a small influence of new technology. With things like Uber making rides more available more quickly and Amazon delivering more things to your door, it may actually be easier to function without a license than it was 10 years ago. Even the general shift from “have to go out to do anything fun” to “can stay home and entertain myself on line” may account for a bit of the decreased enthusiasm for getting licensed to drive. For any one person it’s doubtful that’s the whole reason, but for a few it may be enough to tip the scales.

It will be interesting to see if this corrects itself at some point…will those not getting their license at 18 now get it at 28 instead, or will they forego it entirely? The initial survey most (about 2/3rds) still plan on pursuing one at some point, but whether or not that happens remains to be seen.