Birth order is a hot topic in my family. I’m the oldest of four, and for as long as I can remember I’ve been grousing that being the oldest child is a bad deal. Your parents try out all their bright shiny untested parenting theories on you, relaxing the rules for all the subsequent kids, you’re held responsible for everything, and generally it’s just not faaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaair. Of course all this extra pressure does have some upsides later in life, like an increased likelihood of being a CEO or President. Anyway, given how often I’ve brought this up over the years, my parents (a youngest-of-3 and middle-of-5, respectively) were quick to point me to this article about the disappearance of the middle child in the US. After reading this article and the AVIs post about birthrates earlier this week, I went on a bit of a Google-bender on the whole topic. I figured I’d do a roundup of the most interesting numbers I found.

A quick note before I get started: for ease-of-counting purposes, fertility rates and family sizes are normally measured by “number of kids per woman”. This makes the data less messy, since you don’t have to worry about controlling for people who have children with multiple partners. However, it does often make discussions of fertility rates sound as though women are having kids in a vacuum and that men have nothing to do with it. This is simply not true. Social and economic pressures that encourage women to have fewer kids are almost certainly impacting men as well, and the compounding effect can decrease birthrates quite quickly. So basically while I’ll be making a lot of references to women below, that’s just a data thing, not a “this is how it actually works” thing. Also, I’m going to mostly stick to numbers here as opposed to speculate on causality, because that’s just how I roll.

Alright, with that out of the way, let’s get started!

- Birthrates are declining worldwide. It’s not surprising that most discussions of birthrates and family size in the US immediately start with a discussion of the factors in the US that could have led to falling birthrates. However, it’s important to realize that declining fertility rates is a global phenomena. Our World in Data shows that in 1950, the total fertility rate (TFR) for women everywhere was 5 children. In 2015, it was at 2.49. In that same time period, the US went from about 3 children per woman to 1.84. This is notable because sometimes the explanations that are offered for declining birthrates in the US (like expensive daycare or lack of parental leave policies) don’t hold when you compare them to other countries. Sweden and Denmark are both known for having robust childcare/time off policies for parents, yet their fertility rates are identical to or lower than ours. Whatever it is that pushes birth rates lower, it seems to have a pretty cross cultural impact.

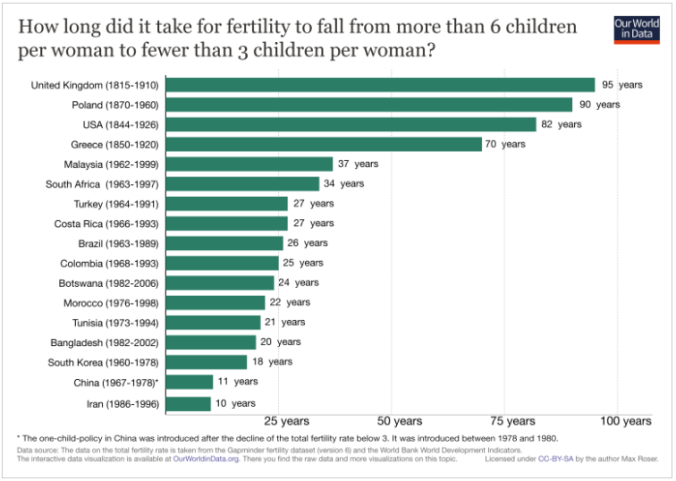

- Birthrates can fall fast. Like, really really fast. Growing up in the US, I always thought of birthrates as something that sort of slowly trended downward as countries grew more developed. What I didn’t realize is that it doesn’t always happen this way. Our World in Data has an interesting chart that shows how long it took for various countries to go from a birthrate of 6 or more children to 3 or fewer:

What’s stunning about this is that some of these numbers are half a generation. For birthrates to fall that quickly in Iran for example, it doesn’t just mean women were having fewer children than their mothers, it means they started having fewer children than their older sisters. In case you’re curious if these trends were just a product of instability in those countries during those times: today the birthrate in Bangladesh is 2.17, South Korea is 1.26, China is 1.60, Iran is 1.97 (per Wiki/CIA Factbook). It seems like all the downward trends shown here kept up or accelerated. China obviously made this a formal policy, but it does not appear the other countries did. I found this interesting because we often hear about subtle factors/cultural messages that impact birthrates, but there’s nothing subtle about these drop offs.

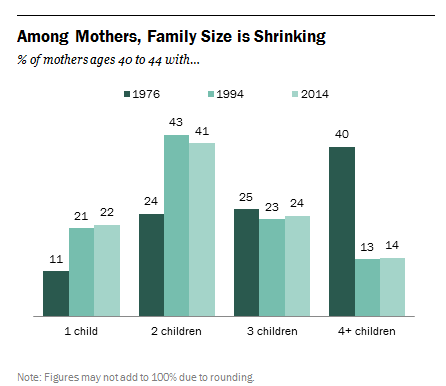

What’s stunning about this is that some of these numbers are half a generation. For birthrates to fall that quickly in Iran for example, it doesn’t just mean women were having fewer children than their mothers, it means they started having fewer children than their older sisters. In case you’re curious if these trends were just a product of instability in those countries during those times: today the birthrate in Bangladesh is 2.17, South Korea is 1.26, China is 1.60, Iran is 1.97 (per Wiki/CIA Factbook). It seems like all the downward trends shown here kept up or accelerated. China obviously made this a formal policy, but it does not appear the other countries did. I found this interesting because we often hear about subtle factors/cultural messages that impact birthrates, but there’s nothing subtle about these drop offs. - A reduction in those having large families impacts the average as much (or more) than the number of women going childless. One of the first things that comes up when you talk about dropping fertility rates is the number of women who remain childless. While childless women certainly cause a drop in fertility rates, it’s important to note that they are also lowered by the number of women who don’t have large numbers of kids. I don’t have the numbers, but I would guess that the countries in point #2 ended up with lower fertility rates not because of a surge in childless women, but by a major decrease in women having 6 or more children. If we look at the change in family size in the US since 1976, the most notable drop is women having 4+ kids. From Pew Research:

My first takeaway from this is that the appeal of having 3 children is timeless. My second takeaway is that it appears a large number of people aren’t crazy about having a large family. This matches my experience, because while you often hear people ask those without children or with one child “why don’t you have more kids?” you don’t often hear people ask those with 2 children the same thing. My friends with 3 children inform me that they actually start getting”you’re not having more are you?” type comments and I’d imagine those with 4 or more get the same thing routinely. Now I grew up going to Baptist school and my siblings were all home schooled at some point, so I am well aware that there are still groups that support/encourage big families. However, even among those who like “big families”, I think the perception of what “big” is has shrunk. I have friends who talked incessantly about wanting big families, married early and were stay at home moms, and none of them have more than 5 children. Most of us don’t have to go more than a generation or two back in our family trees to find a family of 5 kids or more. It seems like even those who want a big family think of it in terms of “more children than others” as opposed to an absolute number. Yes, the Duggars exist, but they are so rare they got a TV show out of the whole thing.

My first takeaway from this is that the appeal of having 3 children is timeless. My second takeaway is that it appears a large number of people aren’t crazy about having a large family. This matches my experience, because while you often hear people ask those without children or with one child “why don’t you have more kids?” you don’t often hear people ask those with 2 children the same thing. My friends with 3 children inform me that they actually start getting”you’re not having more are you?” type comments and I’d imagine those with 4 or more get the same thing routinely. Now I grew up going to Baptist school and my siblings were all home schooled at some point, so I am well aware that there are still groups that support/encourage big families. However, even among those who like “big families”, I think the perception of what “big” is has shrunk. I have friends who talked incessantly about wanting big families, married early and were stay at home moms, and none of them have more than 5 children. Most of us don’t have to go more than a generation or two back in our family trees to find a family of 5 kids or more. It seems like even those who want a big family think of it in terms of “more children than others” as opposed to an absolute number. Yes, the Duggars exist, but they are so rare they got a TV show out of the whole thing. - International adoption likely doesn’t get factored in. As mentioned above, I probably know an above average number of people with 4+ children. Many of these families have a mix of biological and adopted children, frequently foreign adoptions. According the the CDC though, it doesn’t appear those adopted children are not counted in birthrate data, as they calculate that off of birth certificates issued for live births taking place in the US during a given year. Now of course this isn’t a huge impact on overall numbers: there are currently only about 5,000 international adoptions/year in the US, down from a high of 15,000 or so, vs 4,000,000 overall births. However, it is interesting to note that “number of kids” does not always equal birthrate. Since the US is the biggest adopter of foreign children in the world, it is a thing to keep in mind here.

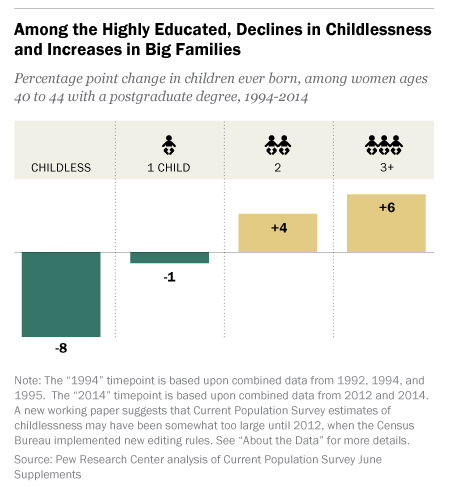

- The demographics of who doesn’t have kids are changing When you mention “women without children” the vision that immediately springs to mind is a well educated white woman who put her career first. Interestingly enough, this stereotype is increasingly untrue, and is changing in many countries. According to Pew Research, childlessness among women with post-graduate degrees has dropped quite a bit in the last 20 years, and the number of women in that group with 3+ kids has gone up:

According to the Economist, in Finland women with a basic education are less likely to have children than their more educated peers, and other countries are trending the same way. The US is nowhere near flipping, but it is an interesting trend to keep an eye on. Historically, education has always been associated with dropping fertility rates, so this would be huge if it switched.

According to the Economist, in Finland women with a basic education are less likely to have children than their more educated peers, and other countries are trending the same way. The US is nowhere near flipping, but it is an interesting trend to keep an eye on. Historically, education has always been associated with dropping fertility rates, so this would be huge if it switched.

Overall, I thought the data out there on the topic was pretty interesting. The worldwide trends make it interesting to try to come up with a hypothesis that fits all scenarios. For example, we know that effective birth control must impact the number of children people have, but Britain and the US both had birthrates under 3 decades before oral contraceptives came in to play. Economic resources must play a part, and yet it’s the richest countries that have the lowest birthrates. Wealth is sometimes linked to higher numbers of children (particularly among men), but sometimes it’s not. Education always lowers fertility rates, except that’s started to reverse. Things to puzzle over.

Anecdote, so not a data point: Maybe twenty years after graduation from dental school, we received a newsletter that had a round-up of what the 105 graduates of that year were doing. Of the dentists and spouses that had children, most of them had one. Two or three had two. And then there was us with five children (two adopted). We were the only ones with that number. There were no three or four child families, and certainly none above me. Of course, we were also in that demographic of homeschooling families. Of my five children, three have their own children: two each. None of them homeschooling.

LikeLike

Interesting! Wonder what those numbers would be today.

Your last comment is interesting, because as I think about the “big family” people in my peer group, I note they all came from 3 child families. In my small sample size, those who came from 4+ child families all went smaller in family size. Again, anecdotes, but it’s interesting to think about.

LikeLike

James had an interesting story about Brazil and soap operas over at my link.

LikeLike

There is an odd paradox. Having children at all is a sign of optimism, but limiting the size of families occurs when couples believe their children have a shot at grabbing the brass ring, thought it will take a lot of resources to launch them. Neither optimism nor pessimism, social mobility or rigid hierarchy, explains what is going on.

LikeLike

That’s the same feeling I have. I almost do wonder if there’s some biological thing…some hormone we make more of when we encounter lots of people or something….that decreases the desire to have children. Something that evolved to keep the population at sustainable levels or something.

That’s probably way too far on the speculation/just so story scale, but it does feel a little too baffling predictable to be a purely psychological phenomena.

LikeLike

That was one of my first thoughts too–remembering the overcrowded mouse experiments–but the rural/urban birth rates don’t seem to show that sort of trend in a consistent way from country to country. Maybe if I dug into it in detail something would show up. The plots of rural/suburban/urban teen birth rates in the US that I saw showed parallel declines in all three.

Some animals won’t breed in captivity. Maybe they need space?

LikeLike

Yeah, and there are quite a few absurdly crowded 3rd world cities that still see higher birthrates than Boston, London, etc.

I was interested to see that education had such an enormous impact, and that it was always downward. Most teachers would kill for that kind of success with anything, so it doesn’t look like it’s the message necessarily, but more the process of being educated that does something.

The most interesting theory I found was that the theory of “kin influence”. Basically, the more time you spend around those who are related to you somehow, the more children you have. When your social network expands, you lose that influence. With this view, it’s not that education reduces fertility by anything it adds, but more by what it removes: time with your kin. If we think about the first stages of development, I think this makes sense. With no schooling, girls in particular are mostly taught how to keep house and care for children. Taking 6-8 hours a day to teach them how to read stops a good chunk of that. The evolutionary theory is that your DNA relatives have a motivation to encourage you to have more children, those unrelated to you do not.

http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1207/s15327957pspr0904_5

There’s been some research done on this in the developed world as well, and it looks like having close family members nearby does seem to increase the likelihood of a second child: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3596370/

Given this, the relevant question may not be “what does development add” but more “what does development remove”. Given that childbirth was the number one cause of female mortality for thousands of years, there may be some sort of natural aversion to multiple pregnancies. Again, given the mortality rates and lack of birth control that we all evolved with, a tendency towards avoiding pregnancy may have been adaptive and helped people space pregnancies more effectively. Now that we don’t die in childbirth, can control getting pregnant with (relative) ease and have large non-kin social networks who are neutral on the topic, this adaptive trait now looks strange.

Again, all speculation, but it’s interesting to think about.

LikeLike

Some additional pressures – young women avoiding pregnancy and delaying marriage shortens the time window for childbearing, older women have more difficulty getting and remaining pregnant, fertility treatments and extraordinary measures to conceive add to the cost. I have heard rumblings (I’d need to do some googling) that male fertility has been on a downward slope for some time so Bethany is probably correct that it’s not just women. My impression is that, though western countries are leading, marriage rates are also dropping worldwide, and I would suspect (though I don’t have data) that women in uncommitted relationships are more likely to try to avoid pregnancy than ones in a traditional marriage.

LikeLike

I was thinking about the later marriage as it impacts the “why don’t women have 4+ kids anymore” question. Starting at 30 probably won’t impact your ability to have 1 child or even 2, but it will make 4 or 5 a lot less likely for a multitude of reasons.

As for your thought on men….my googling says good call 🙂

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3253726/

Key finding “After adjusting for female age, conception during a 12-month period was 30% less likely for men over age 40 years as compared with men younger than age 30 years.”

LikeLike

This is what I was thinking of, though fertility dropping by age would be a factor, too.

http://time.com/4871540/infertility-men-sperm-count/

Men’s sperm counts are said to be dropping over the same time period.

LikeLike

Interesting….had not seen this!

LikeLike

I had seen the sperm count dropping news stories over the last few years. When I saw the numbers in the “Why We Sleep” book, it looked like reduced sleep may account for half the explanation all by itself.

LikeLike

Interesting! I finally read that book, btw. A quick google informs me that sleep deprivation also lowers certain hormones for women, like LH.

This gets me back to my “maybe there’s something that impacts our overall desire to have children going on” thing. We know about things like reduced sperm counts and changes in hormones in women in part because of fertility clinics for those looking to get pregnant, but what about those who may not be? Are parents who had two kids less likely to consider a third because of low hormones that will never be diagnosed? I have never seen any data that both measured sperm count and asked about desire to have children, but it strikes me that they might be linked on a broad population level, with some equivalent for women. We wouldn’t know though, because the group that gets those levels tested are self selected for those who want kids. I doubt any of this would be a strong correlation, but even a moderate population-wide impact might have some effect.

LikeLike

WRT “kin influence” I wonder how much the time spent watching TV cuts down on the time with kin.

When it’s a novelty TV is more of a shared experience, but with less interaction than before. When it’s no longer a novelty it seems (in my limited observations) that people are more willing to interrupt it to interact with each other, but also more likely to watch alone.

LikeLike

Good questions….and an important point that with education comes development which comes with other distractions. The amount of “kin influence” time can drop precipitously.

LikeLike

Pingback: 5 More Things About Fertility Rates | graph paper diaries