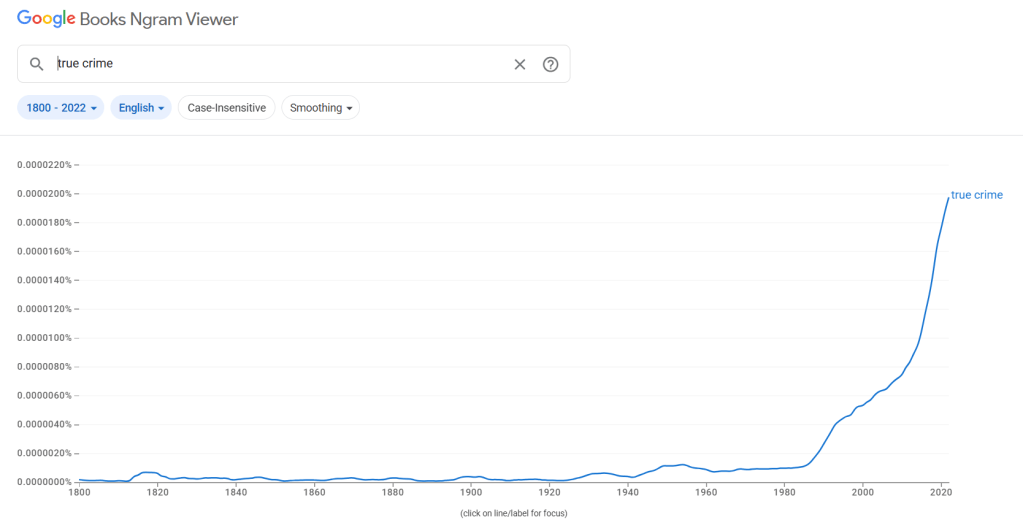

Welcome back! Last week we covered the proposed historical and sociological causes of the replication crisis and applied it to things we see in the true crime genre, and this week we’ll be doing a similar analysis with the group of causes under “problems with the publication system”. As a reminder, I’m loosely following the order in the replication crisis Wiki page, so if you want more you can go there. There’s about 6 reasons listed under the “problems with the publication system” section, so we’ll be taking those one at a time.

Publication Bias

Publication bias in science is a topic I’ve written a lot about over the years, but perhaps my most succinct post was when I covered it during my review of the Calling Bullshit course, where they did a whole class on it. I think the second paragraph I wrote during that post broke it down nicely:

This week we’re taking a look at publication bias, and all the problems that can cause. And what is publication bias? As one of the readings so succinctly puts it, publication bias “arises when the probability that a scientific study is published is not independent of its results.” This is a problem because it not only skews our view of what the science actually says, but also is troubling because most of us have no way of gauging how extensive an issue it is. How do you go about figuring out what you’re not seeing?

In science, some of the findings were skewed by people being more interested in doing novel research rather than trying to replicate others findings, the “file drawer effect” where papers that didn’t find an association between two factors were much less likely to be published, and (outside of science) the fact that the media will mostly focus on unusual findings rather than the full body of scientific literature. My guess is you already see where this is going, but lets think how this applies to true crime.

One of the first thing anyone who looks at true crime as a genre starts to realize is that the crimes covered by traditional true crime are almost never the most common type of crimes. While there’s no “average” homicide, there is certainly a “modal” one! If you were going to describe a typical homicide in the US, most people would pretty quickly come up with something close to this: a young adult man, shot with a handgun, by another young adult man he knows, during an argument or dispute, in a city setting.

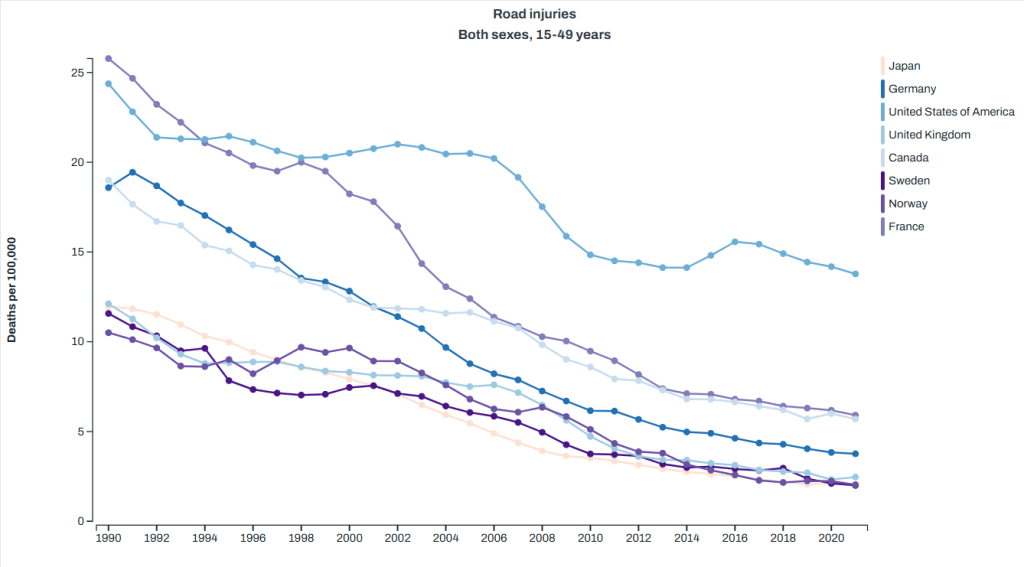

Looking at the stats, we see why this would come to mind: about 80% of homicide victims are male, about 90% of perpetrators are male. Age-wise, crime is dominated by the young. The FBI data also tells us that firearms are used in about 73% of homicides, that you are much more likely to be killed by someone you know than someone you don’t know, and just based on population density alone we would assume most homicides happen in crowded cities. I didn’t include race in the “modal” case because it’s actually closer to 50/50 black vs white, but both homicide victims and perpetrators are disproportionately black. Now there’s a lot of holes in this data because we don’t always know who killed someone, but I think most people would agree based on the general news that these data match what we assume.

If you listen to true crime though? You won’t find that type of crime represented almost at all. I think nearly everyone who’s ever glanced at the news knows if you go missing, heaven help you if you’re anything other than a young attractive white woman, and true crime’s racism problem has been remarked upon for years. I asked ChatGPT which 20 true crime cases it thought got the most media attention in the US (post-1980), and it’s pretty clear these cases caught fire in part because they are so unlike the “typical” crime:

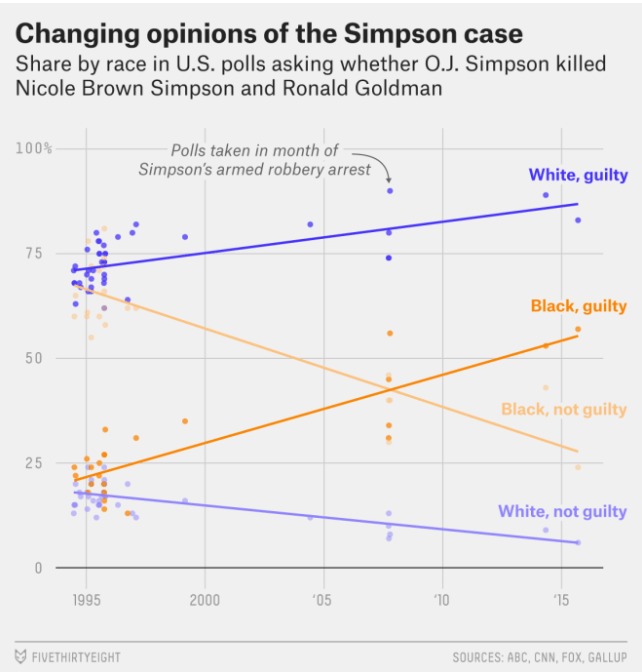

- OJ Simpson Trial (1994-95): famous defendant, white female victim, knife violence

- JonBenet Ramsey (1996): white female child victim, wealthy family, beauty pageants, strangled

- Menendez Brothers (1989): Wealthy family, kids murdering parents

- Jeffrey Dahmer (1991): Male victims, gay sex, cannibalism

- Casey Anthony (2008): Attractive female defendant, white female child victim, strangulation

- Scott Peterson (2002): White female pregnant victim, knife victim

- Central Park Five (1989): white female victim, not murdered

- Amanda Knox (2007): white female victim, white female defendant, stabbed

- Michael Jackson child abuse trials (1993, 2005): celebrity defendant

- OJ Simpson Robbery case (2007): famous defendant, already accused of a crime

- BTK Killer (2005): Serial killer

- Richard Ramirez “Night Stalker” (1980s): serial killer

- Waco Siege (1993): Mass death, cult

- Columbine high (1999): large school shooting

- Unabomber (1996): Mass death

- Tylenol murders (1982): multiple dead, unknown culprit

- Jodi Arias (2008): white female defendant

- Gabby Petito (2021): white female victim, social media star victim

- Michael Skakel/Martha Moxley: Kennedy connection for defendant

- Pamela Smart (1990): white female defendant

What’s interesting about this list is immediately a few things jump out: gun violence is very underrepresented with only a few cases (Menendez brothers, Pam Smart, Columbine, sort of Jodi Arias) involving a firearm. Outside of the mass deaths/serial killers, almost all of the cases involve someone who was at least middle class or higher. Very few cases involve a solo male victim, it’s mostly solo females or men dying in mixed groups. The exceptions are actually 2 cases where there were accusations of homosexuality (Dahmer, Jackson), and the remaining one is Pam Smart’s husband. There’s also a dearth of black or Hispanic victims by themselves, they only appear in groups. In other words, it’s pretty clear the true crime genre does not get hooked on your “average” crimes, they want the unusual ones. I asked Chat GPT what the modal true crime case was, and it summed it up this way: A White, female (often young) victim, killed in a domestic or intimate context, often by a male partner/family member, in an otherwise “safe” suburban setting. The perpetrator is either wealthy/celebrity or a seemingly ordinary middle-class person hiding darkness. The case includes salacious details, a highly publicized trial, and often an ambiguous or polarizing outcome.

Seems about right.

The problem here is if one pays attention to true crime, you are getting an inaccurate view of how crimes are committed and who the victims are. I think this not only skews people’s perception of their own risk of being a victim, but also people getting weirdly judgmental of police departments. Once I started poking around at older true crime cases, I found that an incredibly common criticism is when police treat a big unusual case as though it was going to be a normal case. Well, yeah. Even large police departments may not be prepared for a celebrity perpetrator, simply because we don’t have too many celebrities running around killing people. The day the call comes in for a surprisingly big case, no one flags for the police “actually better send your best guys down there and double the amount of resources available, this case is going to be on Dateline next year”. They are operating under the assumption they will be responding to the modal crime story, true crimers believe they should have been prepping for the modal true crime story.

I also think it’s very relevant how many of these cases happen in quiet suburbs or small towns. In the case I’ve become familiar with, we’ve had 4 murders here in 40 years, and our county has a murder rate of 1/100,000 a year. That’s on par with the safest countries in the world. The idea that taxpayers were going to pay through the nose to keep our police department in a constant state of readiness for unusual events disregards how most taxpayers actually function. Indeed, there was an audit done on our local police department during all this, and one of their conclusions was “if you want your police trained for unusual events, you’re going to have to increase their training budget so they can go do that” and people FLIPPED OUT. And these were the people who were most viciously critiquing the police! Even after years of unrest they were still unwilling to increase the training budget, believe that (as one person actually publicly put it) “you can just watch CSI to know what you should do”. Sure, and you can skip medical school if you watch old ER reruns.

And finally, I think a lot of people justify the focus on white wealthy attractive people with a sort of “trickle down justice system” type philosophy. If we can only monitor how the police handle the most vaunted in our society, this will somehow trickle down to help the poor and the marginalized. The problem is, I’ve never seen particular evidence that’s true. How did the myriad of resources poured in to JonBenet Ramsey’s case help anyone? I grew up near Pam Smart, and I don’t recall that case making much difference after things settled down. Indeed, I think these cases often give us a false impression of what accused killers and victims “worthy” of sympathy look like. Indeed, attractive people are much more likely to get preferential treatment in every part of the justice system. They are arrested less often, convicted less often, and get shorter sentences when they do. It’s hard to get numbers on what percent have a college degree, but even the most generous estimates suggest it’s around 6% of inmates compared to 37% of the general population. The pre-jail income average for prisoners is about $19k a year. Wealthy educated attractive people have very little trouble getting their stories boosted, the people who need help are those not in those groups.

All of this to say, listening constantly to a non-random assortment of cases is not going to give you a good sense of how our justice system works on a day to day basis, any more than only publishing (or pushing) flashy science results gave us a sense of scientific fields. As a pro-tip, when you hear about a case that’s gaining traction, it’s not a bad idea to try to find a couple similar non-famous cases with victims/perpetrators who aren’t wealthy or attractive to see how those cases were handled. Your concerns may remain, but at least it will give you a baseline to work from that typical true crime reporting lacks.

Mathematical Errors

One interesting issue that has played in to a few replication attempts seems almost too silly to mention, but typos and other errors can and do end up influencing papers and their published conclusions. Within the past few days I’ve actually seen this happen at work when we found out that an abstract had the wrong units for a medication dose we wanted to add to a regimen. The typo was mg vs g, so it would have been a very easy typo to make and a pretty disastrous issue for patients. So at least a few replications might fail due to simple human errors in pulling together the information. For example, an oft quoted study saying that men frequently leave their wives when they are diagnosed with cancer was quickly retracted when it was found the whole result was a coding error. The error was regrettable, but what’s even worse is I still see the original finding quoted any time the topic comes up. It’s not true. It was never true, the finding would definitely not replicate. Even the authors admit this, but the rumor doesn’t die.

So how does this relate to true crime? In almost every major case I’ve peaked at, rumors get going about things that did/didn’t happen, and it is very hard to kill them once they’ve started. One good example is actually the Michael Brown/Ferguson case, where it was initially reported he said something like “Hands Up, Don’t Shoot”, a phrase so popular it now has it’s own Wikipedia page. The problem? It doesn’t exist. When the DOJ looked in to the whole thing, the witness who initially said it happened no longer said it did, none of the evidence matched this account, and it’s considered so debunked even the Washington Post ran an article titled “Hands up Don’t Shoot Did not happen in Ferguson“. For the public though? This is considered gospel. I’ve told a few people in the past few years that this didn’t happen, and they look at me like I kicked a puppy. When I’ve pulled up the WaPo headline, Wiki page or DOJ report, they’re still convinced something is wrong. How is it possible something so repeated just…didn’t happen?

I’m not sure but this is way way way more common in true crime reporting than anyone wants to believe, especially on the internet. Shortly after my local case was resolved I saw a Reddit thread about it on a non-true crime subreddit, and people were naming the evidence that most convinced them of their opinion, 7 out of the first ten things listed didn’t occur. And I’m not talking “are disputed” didn’t occur, I’m talking “both the defense and prosecution would look at you like a crazy person if you made these claims in court” stuff. People were publicly proclaiming they’d based a guilt or innocence opinion on stuff they’d never checked out. Since then I play a game in my head every time I talk to someone about the case, I count how many pieces of evidence they mention before they get to one that’s entirely made up. 90% of people don’t get past their third piece of evidence before they quote something made up. That is…not great.

Interestingly when I’ve corrected people, they generally look at me like I’ve missed the point and I’m dwelling on trivialities. To that I have two responses:

- If it’s worth your time to lie about it, it’s worth my time to correct you.

- If I were being accused of a heinous crime I didn’t do, whether in court or just in public opinion, I would want people to correctly quote the evidence against me. So would you. So would everyone. These are real people’s lives, this is not a TV show plot you’re only half remembering.

It’s totally fine in my mind not to be super familiar with any famous public case btw, but if you’re going to speak on it and declare you have a strong opinion, you may want to make sure all of your foundational facts are true. With the internet providing so much of our information now, it is really easy to mistakenly quote something you saw someone tweet about rather than something you actually saw testified to.

Publish or Perish Culture

When you take up a career in science, publication is key to career advancement. One of the issues this leads us to is that papers with large or novel findings are far more likely to be published than those that don’t have those qualities. And what’s less interesting than spending tons of time and resources on a study that someone already did just to say “yeah, seems about right, slightly smaller effect size though”. If there’s no particular reward for trying to replicate studies, people aren’t going to do it. And if people aren’t going to do it, you are not going to spend too much time worrying about if your own study can be replicated or not. One can easily see how this would lead to an issue where studies replicated less often than they would in a system that rewarded replication efforts.

So with true crime, the pressure is all on people to make interesting and bold claims about a story to catch eyes. The remedy for this has basically always been defamation claims, and if you think replications are slow and time consuming, boy have I got news for you about defamation claims. Netflix got incredibly sloppy with it’s documentaries and has a stack of lawsuits waiting to get sorted out in court, but progress is glacial.

This problem has been heightened by the influx of small creators who don’t actually have a lot to lose in court. If you work for the NYTs and report something wrong, your employer takes the hit. If you have a tiktok account you started in your parents basement, you can pretty much say whatever you want knowing no one’s going to spend the cash to go after you. This is starting to change as people realize they need to send messages to these content creators who make reckless accusations, but change is slow. Even true crime podcast redditors have wondered how some of the hosts get away with saying all the stuff they do and why more people don’t sue. Oh, and now the mainstream media can just report on the social media backlash rather than report on things directly. Covington Catholic helped set some better guidelines for this, but the problem remains that none of this has improved the accuracy of reporting.

Even if the content creators confine themselves to facts, they often aren’t their facts. Like all social media, pumping out weekly content is king, and most people simply do not have time to thoroughly research cases themselves. A surprising number of true crime podcasts have been hit with plagiarism accusations, including one where they were just reading other people’s articles on air without attribution. Given that podcasts often end up licensing their content, this drives a lot of possibly sticky legal issues. So what are the consequences for this? As of right now almost nothing. The podcast named in the article above just removed the episode, and as of this writing is the 6th most listened to podcast in the world. Publish or perish, good research be damned.

All right we have a few more publication issues to cover, but I think I’ve gone on long enough and will save that for next week. Stay safe everyone!

To go straight to part 3, click here.