I talk a lot about ways to be wrong on this blog, and most of them are pretty recognizable logical fallacies or statistical issues. For example, I’ve previously talked about the two ways of being wrong when hypothesis testing that are generally accepted by statisticians. If you don’t feel like clicking, here’s the gist: Type I errors are also known as false positives, or the error of believing something to be true when it is not. Type II errors are the opposite, false negatives, or the error of believing an idea to be false when it is not.

Both of those definitions are really useful when testing a scientific hypothesis, which is why they have formal definitions. Today though, I want to bring up the proposal for there to be a recognized Type III error: correctly answering the wrong question.

Here are a couple of examples:

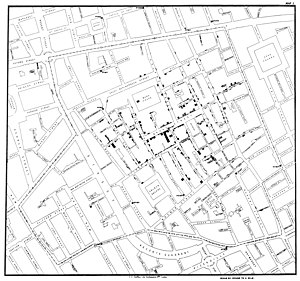

- Drunk Under a Streetlight: Most famously, this could be considered a variant of the streetlight effect. It’s named after this anecdote: “A policeman sees a drunk man searching for something under a streetlight and asks what the drunk has lost. He says he lost his keys and they both look under the streetlight together. After a few minutes the policeman asks if he is sure he lost them here, and the drunk replies, no, and that he lost them in the park. The policeman asks why he is searching here, and the drunk replies, “this is where the light is.”

- Blame it on the GPS: In my “All About that Base Rate” post, I talked about a scenario where the police were testing trash cans for the presence of drugs. A type I error is getting a positive test on a trash can with no drugs in it. A type II error is getting a negative test on a trash can with drugs in it. A type III error would be correctly finding drugs in a trash can at the wrong house.

- Stressing about string theory: James recently had a post about the failure to prove some key aspects of string theory which was great timing since I just finished reading “The Trouble With Physics” and was feeling a bit stressed out by the whole thing. In the book, the author Lee Smolin makes a rather concerning case that we are putting almost all of our theoretical physics eggs in the string theory basket, and we don’t have much to fall back on if we’re wrong. He repeatedly asserts that good science is being done, but that there is very little thought given to the whole “is this the right direction” question.

- Blood Transfusions and Mental Health:The book “Blood Work: A Tale of Medicine and Murder in the Scientific Revolution” provides another example, as it recounts the history of the blood transfusion. Originally, the idea was that transfusions could be used as psychiatric treatments. For many many reasons, this use failed spectacularly enough that they weren’t used again for almost 150 years. At that point someone realized they should try using them to treat blood loss, and the science improved from there.

No matter how good the research was in all of these cases, the answer still wouldn’t have helped answer the larger questions at hand. Like a swimmer in open water, the best techniques in the world don’t help if you’re not headed in the right direction. It sounds obvious, but formalizing a definition like this and teaching it while you teach other techniques might help remind scientists/statisticians to look up every once in a while. You know, just to see where you’re going.