Okay, so after writing 5 Things about Introverts and 5 Things About Extroverts, it has come time for me to talk about MY people: the ambiverts. Sometimes referred to as an introverted extrovert or an extroverted introvert, ambiverts are the people who don’t really fit either mold. So what’s up with this category? Is it a real thing? If it is real is it a good thing? Let’s take a look!

- Ambiversion has been around for a while Okay, so when I first heard about ambiversion, I thought it was a made up thing. Apparently though Carl Jung actually did write about this category when he originally developed the introvert/extrovert scale, though he didn’t name it. According to the Wall Street Journal, the name came about in the 1940s. And to think, I was just blaming Buzzfeed.

- Most people are probably ambiverts If you think of introversion and extroversion as a spectrum of traits, ambiverts are the ones in the middle. It makes sense that most people would be there, though the exact percentage is a little in question: some say 1/3rd of all people, some say 2/3rds. The exact percentage is probably in question because it depends where you draw the line. If you’re 40-60% extroverted, does that make you an ambivert, or is it 35-65%? Regardless, it’s probably not a small number.

- The Big 5 recognizes them, Myers Briggs not so much One of the reasons ambiversion doesn’t get much press is because Myers Briggs (the 500 lb gorilla in the personality testing room) doesn’t really recognize it. Where the Big 5 Personality Scale is based on a sliding scale and generally recognizes “low” “moderate” and “high” scores, Myers Briggs insists on binary classifications.

- The ability to recognize both sides is probably helpful Not a lot of research has been done in to ambiversion, but the little that has been done suggests good things. When studying salespeople, it was found that ambiverts actually made more money than either introverts or extroverts. The researchers think this is because they can work with both types of people and adapt their style more easily to fit the customer. Obviously there would still be a social intelligence aspect to this, but the ability to vary the approach does seem to have it’s benefits.

- The need for both types of recharging can lead to burnout In my previous posts, I asserted that introverts want people to pay more attention to their strengths, and extroverts want people to pay less attention to their faults. Reading through the things written about ambiverts, I realized that their biggest problem seemed to be paying attention to themselves. If you know you need quiet to recharge, that’s straightforward. If you know you need noise, that’s also straightforward. However, if it kind of depends, you have to make a judgment call…..and you very well could be wrong. A lot.

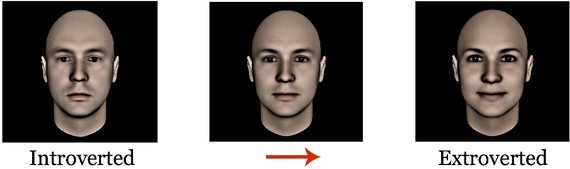

So there you have it! Research in this area is clearly a little light, but I still think it’s interesting to think about how we classify these things. Also, fun fact I learned after writing this….there apparently is an introverted, ambivert and an extroverted facial type:

The article was a little unclear on how good the correlation between facial structure and actual personality type was, but it did raise some questions about the chicken and egg nature of how others perceive us. If someone looks like an extrovert are they more likely to be treated like one and therefore become one? Or is there some “extrovert gene” that determines both? Since all introversion/extroversion measures are self reported it’s hard to know, but it’s an interesting thought. Now I’m gonna go look in the mirror and figure out which type of face I have.

In school settings this is an obvious disadvantage, but in real life may explain why some professions end up extrovert dominated. In many settings, you actually will have to make your toughest calls while there is a lot of noise and chaos around you. By the way, there’s a rather persistent rumor (normally stated in the form of “introverts think more deeply”) that extroverts are less intelligent than introverts. Actually the

In school settings this is an obvious disadvantage, but in real life may explain why some professions end up extrovert dominated. In many settings, you actually will have to make your toughest calls while there is a lot of noise and chaos around you. By the way, there’s a rather persistent rumor (normally stated in the form of “introverts think more deeply”) that extroverts are less intelligent than introverts. Actually the  And here is

And here is

This is all age ranges:

This is all age ranges:  Note: all of those terms were self defined and self reported, and there was no controlling for where those things occurred. In other words, people being called offensive names out of the blue in an innocuous situation were counted the same as someone calling you a name in the middle of a heated debate.

Note: all of those terms were self defined and self reported, and there was no controlling for where those things occurred. In other words, people being called offensive names out of the blue in an innocuous situation were counted the same as someone calling you a name in the middle of a heated debate.