When I first started blogging about correlation and causation (literally my third and fourth post ever), I asserted that there were three possibilities whenever two variables were correlated. Now that I’m older and wiser, I’ve expanded my list to six:

- Thing A caused Thing B (causality)

- Thing B caused Thing A (reversed causality)

- Thing A causes Thing B which then makes Thing A worse (bidirectional causality)

- Thing A causes Thing X causes Thing Y which ends up causing Thing B (indirect causality)

- Some other Thing C is causing both A and B (common cause)

- It’s due to chance (spurious or coincidental)

The obvious conclusion is that years spent blogging about statistics directly correlates to the number of possible ways of confusing correlation and causation you recognize.

Anyway, I’ve talked about this a lot over the years, and this lesson is pretty fundamental in any statistics class…though options #3 and #4 up there aren’t often covered at all. It’s easily forgotten, so I wanted to use this post to pull together an interesting example of each type.

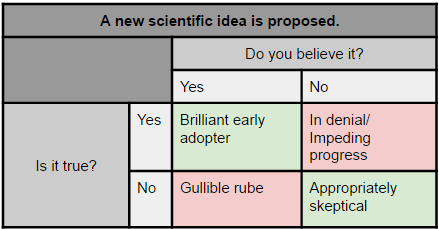

- Smoking cigarettes cause lung cancer (Thing A causes Thing B): This is an example I use in my Intro to Internet Science talk I give to high school students. Despite my continued pleading to be skeptical of various claims, I like to point out that sometimes disbelieving a true claim also has consequences. For years tobacco companies tried to cast doubt on the link between smoking and lung cancer, often using “correlation is not causation!” type propaganda.

- Weight gain in pregnancy and pre-eclampsia (Thing B causes Thing A): This is an interesting case of reversed causation that I blogged about a few years ago. Back in the 1930s or so, doctors had noticed that women who got pre-eclampsia (a potentially life threatening condition) also had rapid weight gain. They assumed the weight gain was causing the pre-eclampsia, and thus told women to severely restrict their weight gain. Unfortunately it was actually the pre-eclampsia causing the weight gain, and it is pretty likely the weight restrictions did more harm than good.

- Dating and desperation (Thing A causes Thing B which makes Thing A worse): We’ve all had that friend. The one who strikes out with everyone they try to date, and then promptly doubles down on their WORST behaviors. This is the guy who stops showering before he takes girls out because “what’s the point”. Or the girl who gets dumped after bringing up marriage on the third date, so she brings it up on the first date instead. This is known as “bidirectional causality” and is less formally known as “a vicious cycle”. In nature this can cause some really amusing graph behavior, as in the case of predators and prey. An increase in prey can cause an increase in predators, but an increase in predators will cause a decrease in prey. Thus, predator and prey populations can be both positively AND negatively correlated, depending on where you are in the cycle.

- Vending machines in Schools and obesity (Thing A causes Thing X causes Thing Y which then causes Thing B): One obvious cause of obesity is eating extra junk food. One obvious source of extra junk food is vending machines. One obvious place to find vending machines is in many schools. So remove vending machines from schools and reduce obesity, right? No, sadly, not that easy. In a longitudinal study that surprised even the authors, it was found that kids who moved from schools without vending machines to those with vending machines don’t gain weight. What’s interesting is that you can find a correlation between kids who were overweight and eating food from vending machines, but it turns out the causal relationship is convoluted enough that removing the vending machines doesn’t actually fix the original end point.

- Vitamins and better health (Some other Thing C is causing Thing A and Thing B):This one is similar to #4, but I consider it more applicable when it turns out Thing A and Thing B weren’t even really connected at all. Eating a bag of chips out of a vending machine every day CAN cause you to gain weight, even if removing the vending machine doesn’t help you lose it again. With many vitamin supplements on the other hand, initial correlations are often completely misleading. Many people who get high levels of certain vitamins (Thing A) are actually just those who pay attention to their health (Thing C), and those people tend to have better health outcomes (Thing B). Not all vitamins should be tarred with the same brush though, this awesome visualization shows where the evidence stands for 100 different supplements.

- Spurious Correlations (spurious or due to chance): There’s a whole website of these, but my favorite is this one:

Causal inference, not for the faint of heart.