My book for this month was supposed to be “In Pursuit of the Unknown: 17 Equations That Changed the World“, but I actually read that a few months ago. It was really good though….an interesting history of mathematical thought, and how some of the famous equations you here about actually influenced human development.

This article is a few years old, but it covers the role of “metascience” in helping with the replication crisis. Metascience is essentially the science of studying science, and it would push researchers to study both their topic AND how experiments about their topic could go wrong. The first suggestion is to have another lab attempt replication before you publish, so you can include possible replication issue in your actual paper right up front.

….and here’s a person actually doing metascience! Yoni Freedhoff, MD is one of my favorite writers on the topic of diet and obesity. He has a great piece up for the Lancet on everything that’s wrong with research in those areas.

On another note entirely….for reasons I’m not even going to try to explain, I am now the proud owner of a Tumblr dedicated to rewriting famous literary quotes to include references to Pumpkin Spice Lattes. It’s called Pumpkin Spiced Literature (obviously), and it’s, um, an acquired taste.

Okay, a doctoral thesis focused on how politicians delete their Tweets is kind of awesome. And yes, Anthony Weiner gets a mention by name. Related: a model of alcoholism that takes Twitter in to account.

On the one hand, I am intrigued by this app. On the other hand, I get sad when people want to shortcut their way out of building better problem solving skills.

This Vanity Fair article about the destruction of Theranos and the downfall of Elizabeth Holmes is incredible, fascinating and a little sad. Particularly intriguing was the quote that undid her: “a chemistry is performed so that a chemical reaction occurs and generates a signal from the chemical interaction with the sample, which is translated into a result, which is then reviewed by certified laboratory personnel.” That made WSJ reporter John Carreyou sit up and say “Huh, I don’t think she knows what she’s talking about”. Seems obvious, but he apparently was the only reporter to figure that out.

Underrated political moment of last week: the New York Times wrote a story about Gary Johnson’s “What is Aleppo?” moment, then has to issue two corrections when it turns out they’re actually not entirely sure what Aleppo is either.

And here is

And here is

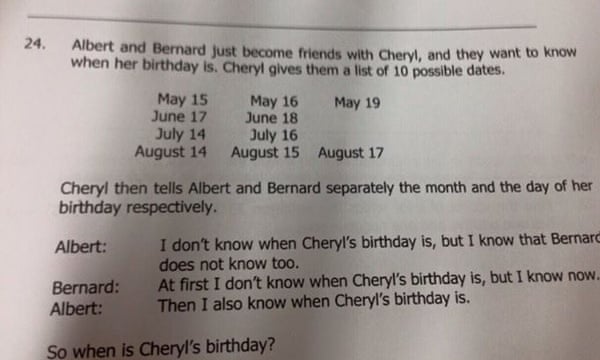

This is all age ranges:

This is all age ranges:  Note: all of those terms were self defined and self reported, and there was no controlling for where those things occurred. In other words, people being called offensive names out of the blue in an innocuous situation were counted the same as someone calling you a name in the middle of a heated debate.

Note: all of those terms were self defined and self reported, and there was no controlling for where those things occurred. In other words, people being called offensive names out of the blue in an innocuous situation were counted the same as someone calling you a name in the middle of a heated debate.