Welcome to “From the Archives”, where I dig up old posts and see what’s changed in the years since I originally wrote them.

I’ve had a rather interesting couple weeks here in my little corner of the blogosphere. A little over a year ago, a reader asked me to write a post about a video he had seen kicking around that used gumballs to illustrate world poverty. With the renewed attention to immigration issues over the last few weeks, that video apparently went viral and brought my post with it. My little blog got an avalanche of traffic and with it came a new series of questions, comments and concerns about my original post. The comments on the original post closed after 90 days, so I was pondering if I should do another post to address some of the questions and concerns I was being sent directly. A particularly long and thoughtful comment from someone named bluecat57 convinced me that was the way to go, and almost 2500 something words later, here we are. As a friendly reminder, this is not a political blog and I am not out to change your mind on immigration to any particular stance. I actually just like talking about how we use numbers to talk about political issues and the fallacies we may encounter there.

Note to bluecat57: A lot of this post will be based on various points you sent me in your comment, but I’m throwing a few other things in there based on things other people sent me, and I’m also heavily summarizing what you said originally. If you want me to post your original comment in the comments section (or if you want to post it yourself) so the context is preserved, I’m happy to do so.

Okay, with that out of the way, let’s take another look at things!

First, a quick summary of my original post: The original post was a review of a video by a man named Roy Beck. The video in question (watch it here) was a demonstration centered around whether or not immigration to the US could reduce world poverty. In it, pulls out a huge number of gumballs, with each one representing 1 million poor people in the world, defined by the World Bank’s cutoff of “living on less than $2/day” and demonstrates that the number of poor people is growing faster than we could possibly curb through immigration. The video is from 2010. My criticisms of the video fell in to 3 main categories:

- The number of poor people was not accurate. I believe it may have been at one point, but since the video is 7 years old and world poverty has been falling rapidly, they are now wildly out of date. I don’t blame Beck for his video aging, but I do get irritated his group continues to post it with no disclaimer.

- That the argument the video starts with “some people say that mass immigration in to the United States can help reduce world poverty” was not a primary argument of pro-immigration groups, and that using it was a strawman.

- That people liked, shared and found this video more convincing than they should have because of the colorful/mathematical demonstration.

My primary reason for posting about the video at all was actually point #3, as talking about how mathematical demonstrations can be used to address various issues is a bit of a hobby of mine. However, it was my commentary on #1 and #2 that seemed to attract most of the attention. So let’s take a look at each of my points, shall we?

Point 1: Poverty measures, and their issues: First things first: when I started writing the original post and realized I couldn’t verify Beck’s numbers, I reached out to him directly through the NumbersUSA website to ask for a source for them. I never received a response. Despite a few people finding old sources that back Beck up, I stand by the assertion that those numbers are not currently correct as he cites them. It is possible to find websites quoting those numbers from the World Bank, but as I mentioned previously, the World Bank itself does not give those numbers. While those numbers may have come from the World Bank at some point he’s out of date by nearly a decade, and it’s a decade in which things have rapidly changed.

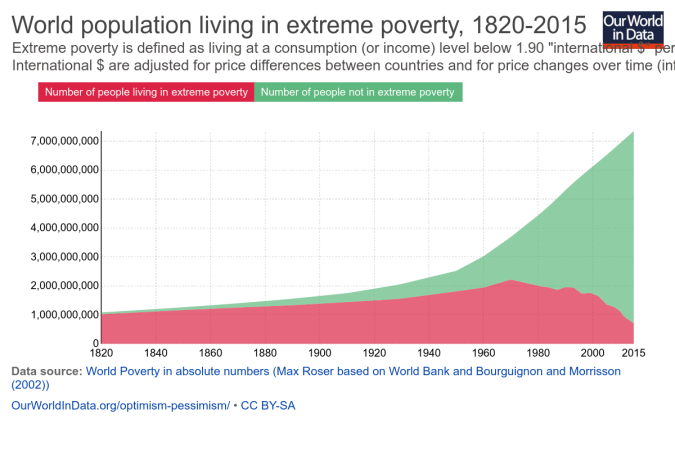

Now this isn’t necessarily his fault. One of the reasons Beck’s numbers were rendered inaccurate so quickly was because reducing extreme world poverty has actually been a bit of a global priority for the last few years. If you were going to make an argument about the number of people living in extreme poverty going up, 2010 was a really bad year to make that argument:

Basically he made the argument in the middle of an unprecedented fall in world poverty. Again, not his fault, but it does suggest why he’s not updating the video. The argument would seem a lot weaker starting out with “there’s 700 million desperately poor people in the world and that number falls by 137,000 people every day”.

Moving on though…is the $2/day measure of poverty a valid one? Since the World Bank and Beck both agreed to use it, I didn’t question it much up front, but at the prompting of commenters, I went looking. There’s an enormously helpful breakdown of global poverty measures here, but here’s the quick version:

- The $2/day metric is a measure of consumption, not income and thus is very sensitive to price inflation. Consumption is used because it (attempts to) account for agrarian societies where people may grow their own food but not earn much money.

- Numbers are based on individual countries self-reporting. This puts some serious holes in the data.

- The definition is set based on what it takes to be considered poor in the poorest countries in the world. This caused it’s own problems.

That last point is important enough that the World Bank revised it’s calculation method in 2015, which explains why I couldn’t find Beck’s older numbers anywhere on the World Bank website. Prior to that, it set the benchmark for extreme poverty based off the average poverty line used by the 15 poorest countries in the world. The trouble with that measure is that someone will always be the poorest, and therefore we would never be rid of poverty. This is what is known as “relative poverty”.

Given that one of the Millennium Development Goals focused on eliminating world poverty, the World Bank decided to update it’s estimates to simply adjust for inflation. This shifts the focus to absolute poverty, or the number of people living below a single dollar amount. Neither method is perfect, but something had to be picked.

It is worth noting that country self reports can vary wildly, and asking the World Bank to put together a single number is no small task. While the numbers presented, it is worth noting that even small revisions to definitions could cause huge change. Additionally, none of these numbers address country stability, and it is quite likely that unstable countries with violent conflicts won’t report their numbers. It’s also unclear to me where charity or NGO activity is counted (likely it varies by country).

Interestingly, Politifact looked in to a few other ways of measuring global poverty and found that all of them have shown a reduction in the past 2 decades, though not as large as the World Bank’s. Beck could change his demonstration to use a different metric, but I think the point remains that if his demonstration showed the number of poor people falling rather than rising, it would not be very compelling.

Edit/update: It’s been pointed out to me that at the 2:04 mark he changes from using the $2/day standard to “poorer than Mexico”, so it’s possible the numbers after that timepoint do actually work better than I thought they would. It’s hard to tell without him giving a firm number. For reference, it looks like in 2016 the average income in Mexico is $12,800/year . In terms of a poverty measure, the relative rank of one country against others can be really hard to pin down. If anyone has more information about the state of Mexico’s relative rank in the world, I’d be interested in hearing it.

Point 2: Is it a straw man or not? When I posted my initial piece, I mentioned right up front that I don’t debate immigration that often. Thus, when Beck started his video with “Some people say that mass immigration in to the United States can help reduce world poverty. Is that true? Well, no it’s not. And let me show you why…..” I took him very literally. His demonstration supported that first point, that’s what I focused on. When I mentioned that I didn’t think that was the primary argument being made by pro-immigration groups, I had to go to their mission pages to see what their argument actually were. None mentioned “solving world poverty” as a goal. Thus, I called Beck’s argument a straw man, as it seemed to be refuting an argument that wasn’t being made.

Unsurprisingly, I got a decent amount of pushback over this. Many people far more involved in the immigration debates than I informed me this is exactly what pro-immigration people argue, if not directly then indirectly. One of the reasons I liked bluecat57’s comment so much, is that he gave perhaps the best explanation of this.To quote directly from one message:

“The premise is false. What the pro-immigration people are arguing is that the BEST solution to poverty is to allow people to immigrate to “rich” countries. That is false. The BEST way to end poverty is by helping people get “rich” in the place of their birth.

That the “stated goals” or “arguments” of an organization do not promote immigration as a solution to poverty does NOT mean that in practice or in common belief that poverty reduction is A solution to poverty. That is why I try to always clearly define terms even if everyone THINKS they know what a term means. In general, most people use the confusion caused by lack of definition to support their positions.”

Love the last sentence in particular, and I couldn’t agree more. My “clear definitions” tag is one of my most frequently used for a reason.

In that spirit, I wanted to explain further why I saw this as a straw man, and what my actual definition of a straw man is. Merriam Webster defines a straw man as “a weak or imaginary argument or opponent that is set up to be easily defeated“. If I had ever heard someone arguing for immigration say “well we need it to solve world poverty”, I would have thought that was an incredibly weak argument, for all the reasons Beck goes in to….ie there are simply more poor people than can ever reasonably be absorbed by one (or even several) developed country. Given this, I believe (though haven’t confirmed) that every developed/rich country places a cap on immigration at some point. Thus most of the debates I hear and am interested in are around where to place that cap in specific situations and what to do when people circumvent it. The causes of immigration requests seem mostly debated when it’s in a specific context, not a general world poverty one.

For example, here’s the three main reasons I’ve seen immigration issues hit the news in the last year:

- Illegal immigration from Mexico (too many mentions to link)

- Refugees from violent conflicts such as Syria

- Immigration bans from other countries

Now there are a lot of issues at play with all of these, depending on who you talk to: general immigration policy, executive power, national security, religion, international relations, the feasibility of building a border wall, the list goes on and on. Poverty and economic opportunity are heavily at play for the first one, but so is the issue of “what do we do when people circumvent existing procedures”. In all cases if someone had told me that we should provide amnesty/take in more refugees/lift a travel ban for the purpose of solving world poverty, I would have thought that was a pretty broad/weak argument that didn’t address those issues specifically enough. In other words my characterization of this video as a straw man argument was more about it’s weakness as a pro-immigration argument than a knock against the anti-immigration side. That’s why I went looking for the major pro-immigration organizations official stances….I actually couldn’t believe they would use an argument that weak. I was relieved when I didn’t see any of them advocating this point, because it’s really not a great point. (Happy to update with examples of major players using this argument if you have them, btw).

In addition to the weaknesses of this argument as a pro-immigration point, it’s worth noting that from the “cure world poverty” side it’s pretty weak as well. I mentioned previously that huge progress has been made in reducing world poverty, and the credit for that is primarily given to individual countries boosting their GDP and reducing their internal inequality. Additionally, even given the financial situation in many countries, most people in the world don’t actually want to immigrate. This makes sense to me. I wouldn’t move out of New England unless there was a compelling reason to. It’s home. Thus I would conclude that helping poor countries get on their feet would be a FAR more effective way of eradicating global poverty than allowing more immigration, if one had to pick between the two. It’s worth noting that there’s some debate over the effect of healthy/motivated people immigrating and sending money back to their home country (it drains the country of human capital vs it brings in 3 times more money than foreign aid), but since that wasn’t demonstrated with gumballs I’m not wading in to it.

So yeah, if someone on the pro-immigration side says mass immigration can cure world poverty, go ahead and use this video….keeping in mind of course the previously stated issue with the numbers he quotes. If they’re using a better or more country or situation specific argument though (and good glory I hope they are), then you may want to skip this one.

Now this being a video, I am mindful that Beck has little control over how it gets used and thus may not be at fault for possible straw-manning, any more than I am responsible for the people posting my post on Twitter with Nicki Minaj gifs (though I do love a good Nicki Minaj gif).

Point 3 The Colorful Demonstration: I stand by this point. Demonstrations with colorful balls of things are just entrancing. That’s why I’ve watched this video like 23 times:

Welp, this went on a little longer than I thought. Despite that I’m sure I missed a few things, so feel free to drop them in the comments!