Welcome to “So Why ARE Most Published Research Findings False?”, a step by step walk through of the John Ioannidis paper bearing that name. If you missed the intro, check it out here.

Okay, so last week I gave you the intro to the John Ioannidis paper Why Most Published Research Findings are False. This week we’re going to dive right in with the first section, which is excitingly titled “Modeling the Framework for False Positive Findings“.

Ioannidis opens the paper with a review of the replication crisis (as it stood in 2005 that is) and announces his intention to particularly focus on studies that yield false positive results….aka those papers that find relationships between things where no relationship exists.

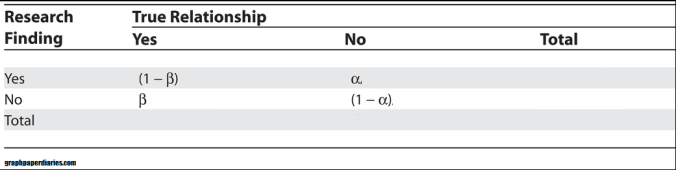

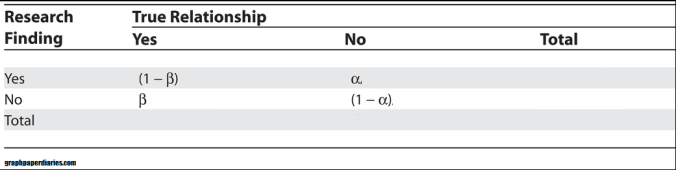

To give a framework for understanding why so many of these false positive findings exists, he creates a table showing the 4 possibilities for research findings, and how to calculate how large each one is. We’ve discussed these four possibilities before, and they look like this:

Now that may not look too shocking off the bat, and if you’re not in to this sort of thing you’re probably yawning a bit. However, for those of us in the stats world, this is a paradigm shift. See historically stats students and researchers have been taught that the table looks like this:

This table represents a lot of the decisions you make right up front in your research, often without putting much thought in to it. Those values are used to drive error rates, study power and confidence intervals:

The alpha value is used to drive the notorious “.05” level used in p-value testing, and is the chances that you would see a relationship more extreme than the one you’re seeing due to random chance.

What Ioannidis is adding in here is c, or the overall number of relationships you are looking at, and the R, which is the overall proportion of true findings to false findings in the field. Put another way, this is the “Pre-Study Odds”. It asks researchers to think about it up front: if you took your whole field and every study ever done in it, what would you say the chances of a positive finding are right off the bat?

Obviously R would be hard to calculate, but it’s a good add in for all researchers. If you have some sense that your field is error prone or that it’s easy to make false discoveries, you should be adjusting your calculations accordingly. Essentially he is asking people to consider the base rate here, and to keep it front and center. For example, a drug company that has carefully vetted it’s drug development process may know that 30% of the drugs that make it to phase 2 trials will ultimately prove to work. On the other hand, a psychologist attempting to create a priming study could expect a much lower rate of success. The harder it is for everyone to find a real relationship, the greater the chances that a relationship you do find will also be a false positive. I think requiring every field to come up with an R would be an enormously helpful step in and of itself, but Ioannidis doesn’t stop there.

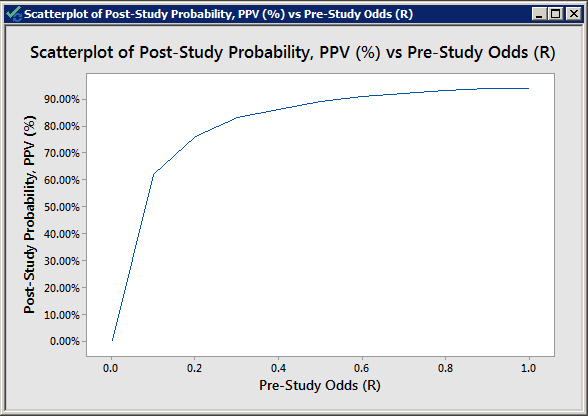

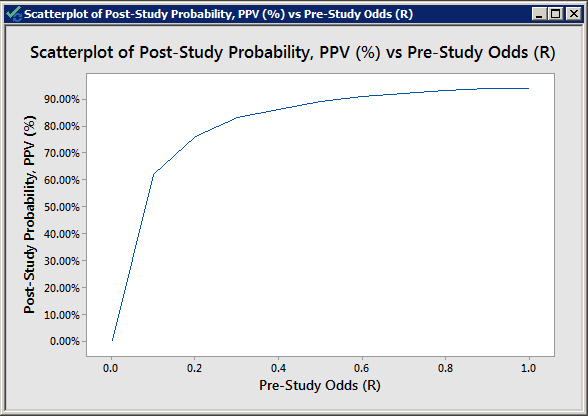

Ultimately, he ends up with an equation for the Positive Predictive Value (aka the chance that a positive result is true aka PPV aka the chance that a paper you read is actually reporting a real finding) which is PPV = (1 – β)R/(R – βR + α). For a study with a typical alpha and a good beta (.05 and .2, respectively), here’s what that looks like for various values of R:

So the lower the pre-study odds of success, the more likely it is that a finding is a false positive rather than a true positive. Makes sense right?

Now most readers will very quickly note that this graph shows that you have a 50% chance of being able to trust the result at a fairly low level of pre-study odds, and that is true. Under this model, the study is more likely to be true than false if (1 – β)R > α. In the case of my graph above, this translates in to pre-study odds that are greater than 1/16. So where do we get the “most findings are false” claim?

Enter bias.

You see, Ioannidis was setting this framework up to remind everyone what the best case scenario was. He starts here to remind everyone that even within a perfect system, some fields are going to be more accurate than others simply due to the nature of the investigations they do, and that no field should ever expect that 100% accuracy is their ceiling. This is an assumption of the statistical methods used, but this assumption is frequently forgotten when people actually sit down to review the literature. Most researchers would not even think of claiming that their pre-study odds were more than 30%, yet very few would say off the top “17% of studies finding significant results in my field are wrong”, yet that’s what the math tells us. And again, that’s in a perfect system. Going forward we’re going to add more terms to the statistical models, and those odds will never get better.

In other words, see you next week folks, it’s all down hill from here.

Click here to go straight to part 2.

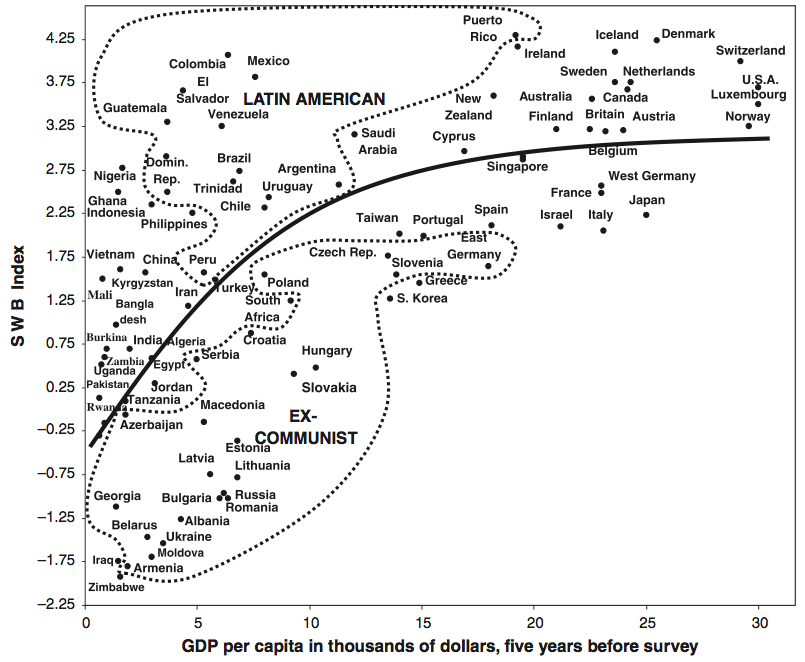

If you think about it, this makes a lot of sense. If money is a struggle, it affects your happiness. Once you’ve stopped struggling, it stops having the same effect. So basically it’s more accurate to say that money can’t buy happiness, but a lack of money sure can stress you out.

If you think about it, this makes a lot of sense. If money is a struggle, it affects your happiness. Once you’ve stopped struggling, it stops having the same effect. So basically it’s more accurate to say that money can’t buy happiness, but a lack of money sure can stress you out. So countries that struggle to develop do take their toll on their citizens, but at some point development stops yielding returns in well being. It would be interesting to see if the effect of personal wealth varied with country GDP, but alas I can’t find that data.

So countries that struggle to develop do take their toll on their citizens, but at some point development stops yielding returns in well being. It would be interesting to see if the effect of personal wealth varied with country GDP, but alas I can’t find that data.