“Terrorism is surging in the US, fueled by right-wing ideologies”

Someone posted this rather eye catching story on Twitter recently, which came from an article back in August from QZ.com. I’ve blogged about how we classify terrorism or other Mass Casualty Incidents over the years, so I decided to click through to the story.

It came with two interesting graphs that I thought warranted a closer look. The first was a chart of all terror incidents (the bars) vs the fatalities in the US:

Now first things first: I always note immediately where the year starts. There’s a good reason this person chose to do 15 years and not 20, because including 9/11 in any breakdown throws the numbers all off. This chart peaks at less than 100 fatalities, and we know 2001 would have had 30 times that number.

Still, I was curious what definition of terrorism was being used, so I went to look at the source data they cited from the Global Terrorism Database. The first thing I noted when I got to the website is that data collection for incidents is open source. Interesting. Cases are added by individual data collectors, then reviewed by those who maintain the site. I immediately wondered exactly how long this had been going on, as it would make sense that more people added more incidents as the internet became more ubiquitous and in years where terrorism hit the news a lot.

Sure enough, on their FAQ page, they actually specifically address this (bolding mine):

Is there a methodological reason for the decline in the data between 1997 and 1998, and the increases since 2008 and 2012?

While efforts have been made to assure the continuity of the data from 1970 to the present, users should keep in mind that the data collection was done as events occurred up to 1997, retrospectively between 1998 and 2007, and again concurrently with the events after 2008. This distinction is important because some media sources have since become unavailable, hampering efforts to collect a complete census of terrorist attacks between 1998 and 2007. Moreover, since moving the ongoing collection of the GTD to the University of Maryland in the Spring of 2012, START staff have made significant improvements to the methodology that is used to compile the database. These changes, which are described both in the GTD codebook and in this START Discussion Point on The Benefits and Drawbacks of Methodological Advancements in Data Collection and Coding: Insights from the Global Terrorism Database (GTD), have improved the comprehensiveness of the database. Thus, users should note that differences in levels of attacks before and after January 1, 1998, before and after April 1, 2008, and before and after January 1, 2012 may be at least partially explained by differences in data collection; and researchers should adjust for these differences when modeling the data.

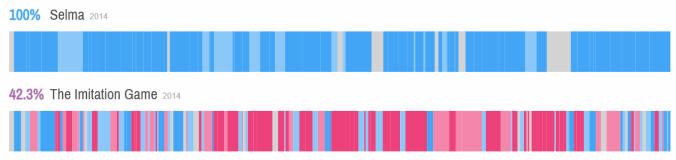

So the surge in incidents might be real, or it might be that they started collecting things more comprehensively, or a combination of both. This is no small matter, as out of the 366 incidents covered by the table above, 266 (72%)had no fatalities. 231 incidents (63%) had no fatalities AND no injuries. Incidents like that are going to be much hard to find records for unless they’re being captured in real time.

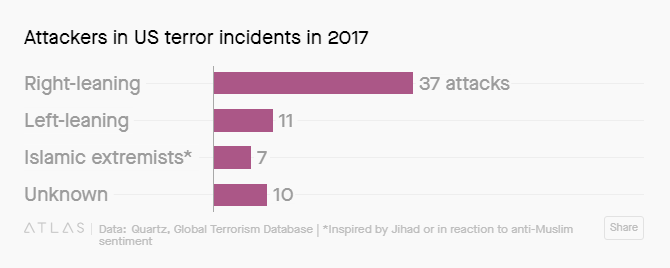

The next graph they featured was this one, where they categorized incidents by perpetrator:

The original database contains a line for “perpetrator group”, which seems to speak loosely to motivation. Overall they had 20 different categories for 2017, and Quartz condensed them in to the 4 above. I started to try to replicate what they did, but immediately got confused because the GTD lists 19 of the groups as “Unknown”, so Quartz had to reassign 9 of them to some other group. Here’s what you get just from the original database:

Keep in mind that these categories are open source, so differences in labeling may be due to different reviewers.

Now it’s possible that information got updated in the press but not in the database. It seems plausible that incidents might be added shortly after they occur, then not reviewed later when more facts were settled. For example, the Las Vegas shooter was counted under “anti-government extremists”, but we know that the FBI closed the case 6 months ago stating they never found a motive. In fact, the report concluded that he had a marked disinterest in political and religious beliefs, which explains his lack of manifesto or other explanation for his behavior. While anti-government views had been floated as a motive originally, that never panned out. Also worth noting, the FBI specifically concluded this incident did not meet their definition for terrorism.

Out of curiosity, I decided to take a look at just the groups that had an injury or fatality associated with their actions (29 out of the 65 listed for 2017):

If you want to look at what incident each thing is referring to, the GTD list is here. Glancing quickly, the one incident listed as explicitly right wing was Mitchell Adkins, who walked in to a building and stabbed 3 people after asking them their political affiliation. The one anti-Republican one was the attack on the Republican Congressional softball team.

I think overall I like the original database categories better than broad left or right wing categories, which do trend towards oversimplification. Additionally, when using crowd sourced information, you have to be careful to account for any biases in reporting. If the people reporting incidents are more likely to come from certain regions or to pay more attention to certain types of crimes, the database will reflect that.

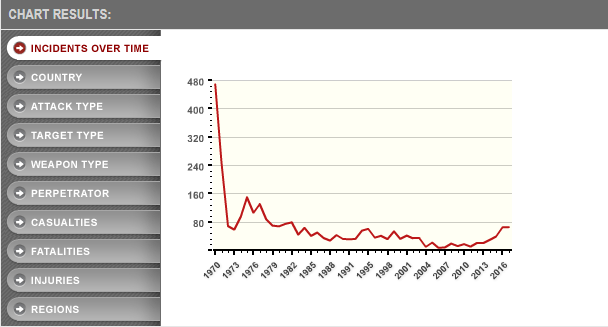

To illustrate that point, I should note that 1970 is by FAR the worst year for terrorist incidents they have listed. Here’s their graph:

Now I have no idea if 1970 was really the worst year on record or if it got a lot of attention for being the first year they started this or if there’s some quirk in the database here, but that spike seems unlikely. From scanning through quickly, it looks like there’s a lot of incidents that happened in the same day. That trend was also present in the current data, and there were a few issues I noted that looked like duplicates but also could have been two things done similarly in the same day.

Overall though, I think comparing 1970 to 2017 shows an odd change in what we call terrorism. Many of the incidents listed in 1970 were done by people who specifically seemed to want to make a point about their group. In 2017, many of the incidents seemed to involve someone who wanted to be famous, and picked their targets based on whoever drew their ire. You can see this by the group names. In 2017 only one named group was responsible for a terrorist attack (the White Rabbit Militia one) whereas in 1970 there at least a dozen groups with names like “New World Liberation Front” or “Armed Revolutionary Independence Movement“.

Overall, this change does make it much harder to figure out what ideological group terrorists belong to, as a large number of them seem to be specifically eschewing group identification. Combine that with the pitfalls of crowd sourcing, and changing definitions, and I’d say this report is somewhat inconclusive.