I’ve been a little slow on this, but I’ve been meaning to get around to the paper “Many Analysts, One Data Set: Making Transparent How Variations in Analytic Choices Affect Results. This paper was published back in August, but I think it’s an important one for anyone looking to understand why science can often be so difficult.

The premise of this paper was simple, but elegant: give 29 teams the same data set and the same question to answer, then see how everyone does their analysis and if all of those analyses yield the same results. In this case, the question was “do soccer referees give red cards to dark skinned players more than light skinned players”. The purpose of the paper was to highlight how seemingly minor choices in data analysis can yield different results, and all participants had volunteered for this study with full knowledge of what the purpose was. So what did they find? Let’s take a look!

-

- Very few teams picked the same analysis methods. Every team in this study was able to pick whatever method they thought best fit the question they were trying to answer, and boy did the choices vary. First, the choice of analysis method varied:

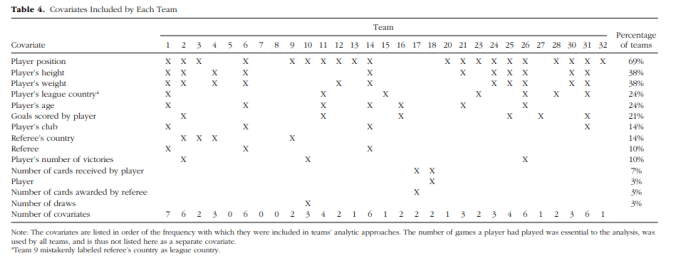

Next, the choice of covariates varied wildly. The data set had contained 14 covariates, and the 29 teams ended up coming up with 21 different combinations to look at:

Next, the choice of covariates varied wildly. The data set had contained 14 covariates, and the 29 teams ended up coming up with 21 different combinations to look at:

- Choices had consequences As you can imagine, this variability produced some interesting consequences. Overall 20 of the 29 teams found a significant effect, but 9 didn’t. The effect sizes they found also varied wildly, with odds ratios running from .89 to 2.93.

While that shows a definite trend in favor of the hypothesis, it’s way less reliable than the p<.05 model would suggest.

While that shows a definite trend in favor of the hypothesis, it’s way less reliable than the p<.05 model would suggest. - Analytic choices didn’t necessarily predict who got a significant result. Now because all of these teams signed up knowing what the point of the study was, the next step in this study was pretty interesting. All the teams methods (but not their results) were presented to all the other teams, who then rated them. The highest rated analyses gave a median odds ratio of 1.31, and the lower rated analyses gave a median odds ratio of…..1.28. The presence of experts on the team didn’t change much either. Teams with previous experience teaching or publishing on statistical methods generated odds ratios with a median of 1.39, and the ones without such members had a median OR of 1.30. They noted that those with statistical expertise seemed to pick more similar methods, but that didn’t necessarily translate in to significant results.

- Researchers beliefs didn’t influence outcomes. Now of course the researchers involved in this had self-selected in a to a study where they knew other teams were doing the same analysis they were, but it’s interesting to note that those who said up front they believed the hypothesis was true were not more likely to get significant results than those who were more neutral. Researchers did change their beliefs over the course of the study however, as this chart showed:

While many of the teams updated their beliefs, it’s good to note that the most likely update was “this is true, but we don’t know why”, followed by “this is true, but may be caused by something we didn’t captured in this data set (like player behavior)”.

While many of the teams updated their beliefs, it’s good to note that the most likely update was “this is true, but we don’t know why”, followed by “this is true, but may be caused by something we didn’t captured in this data set (like player behavior)”. - They key differences in analysis weren’t things most people would pick up on. At one point in the study, the teams were allowed to debate back and forth and look at each others analysis. One researcher noted that those teams that had included league and club as covariates were the ones who got non-significant results. As the paper states “A debate emerged regarding whether the inclusion of these covariates was quantitatively

defensible given that the data on league and club were

available for the time of data collection only and these

variables likely changed over the course of many players’

careers”. This is a fascinating debate, and one that would likely not have happened had these papers just been analyzed by one team. This choice was buried deep in the methods section, and I doubt under normal circumstances anyone would have thought twice about it.

- Very few teams picked the same analysis methods. Every team in this study was able to pick whatever method they thought best fit the question they were trying to answer, and boy did the choices vary. First, the choice of analysis method varied:

That last point gets to why I’m so fascinated by this paper: it shows that lots of well intentioned teams can get different results even if no one is trying to be deceptive. These teams had no motivation to fudge their results or skew anything, and in fact were incentivized in the opposite direction. They still got different results however, for reasons that were so minute and debatable, they had to take multiple teams to discuss them. This shows nicely Andrew Gelman’s Garden of Forking Paths, how small choices can lead to big changes in outcomes. With no standard way of analyzing data, tiny boring looking choices in analysis can actually be a big deal.

The authors of the paper propose more group approaches may help mitigate some of these problems and give us all a better sense of how reliable results really are. After reading this, I’m inclined to agree. Collaborating up front also takes the adversarial part out, as you don’t just have people challenging each others research after the fact. Things to ponder.